Why structural demographic challenges threaten house-building numbers

Much has been made of the latest English Housing Survey that shows homeownership among the young dwindling still further.

It’s a corker for the media. It has generated reams of copy in the press and numerous discussions on TV broadcasts and radio phone-ins.

But it ain’t news.

A bit like the “ageing population problem”, the decline in youngsters owning their own homes was evident decades ago if you cared to look at the statistics.

A favoured quip is that Margaret Thatcher created a generation of homeowners – just the one generation though.

In truth fast-rising homeownership easily pre-dates Thatcher. She did however cash-in on its popularity, promoted the trend and accelerated it by selling council housing.

Today many of those who rode the post-War tidal wave of swelling homeownership are surfing onto the sunbathed equity-rich shores of retirement. Sadly they leave behind them desperate would-like-to-be-homeowners splashing about deep in a trough waiting for the next wave to appear.

You might ask: Why was the media so slow to recognise this long-standing phenomenon? That would be pertinent. An obvious suggestion is that the middle classes have only recently felt a pinch felt many decades ago by poorer fellow citizens – those less active in political and media circles.

You might also reasonably ask: Why is the focus primarily on intergenerational fairness? Good question. There are serious intergenerational issue. They need addressing. But there are deeper structural problems beneath that are disguised by this shallow skim through the data. At least, I think there are. You may think differently.

Let me describe just one of these structural problems I feel are concerning.

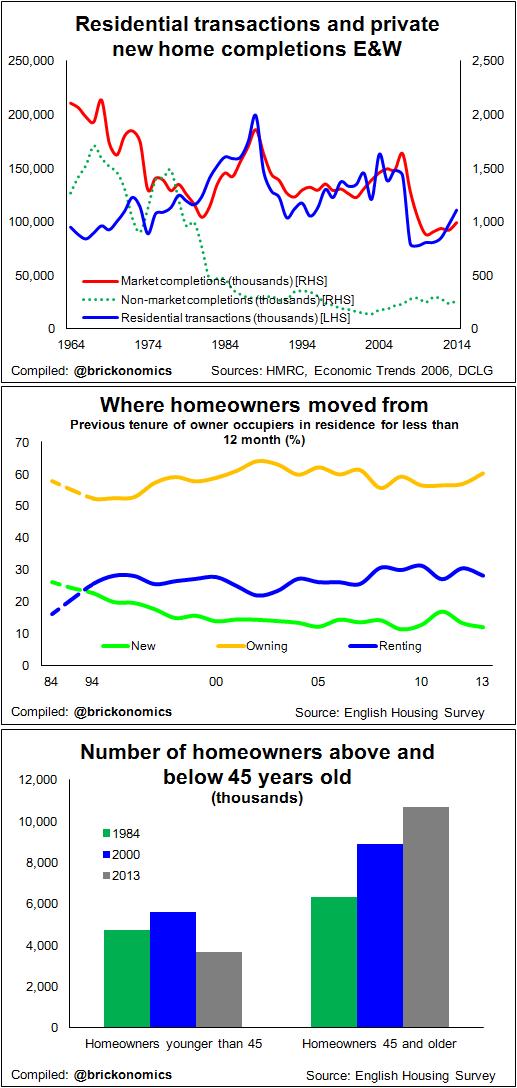

The story starts with the top graph. It’s a favourite of mine. It shows for the past 40 years or so we have built one private new home for every 10 homes sold in the housing market in England and Wales as a whole.

What drives this is not fully clear, to me anyway. That’s why I like it so much. It tweaks my curiosity.

What drives this is not fully clear, to me anyway. That’s why I like it so much. It tweaks my curiosity.

The link maybe in some way connected to planning. Maybe, as the graph seems to intimate, there is a connection to the collapse in social housing provision. Research is needed.

But it’s a remarkably strong and enduring link and as the market is currently structured it’s holding firm.

If we speculate that this link will continue to hold, there appear to be two options for boosting private sector house building.

We could discover what causes this link and break it favourably to boost the market share of new homes, or we could greatly promote more residential transactions.

Given we don’t really know what causes this link to hold (or at least I’ve not seen any solid explanation) it’s hard to know how to break it. So we’re left with finding ways to raise transactions.

Sadly, here, the English Housing Survey data hold bad news in the demographics. They point to things getting worse, because existing homeowners are likely on average to move less and they account for a major share of residential transactions.

The English House Survey and its predecessor the Survey of English Housing suggest that 60% of people that move into or within homeownership are previous homeowners. The second graph shows how this has been pretty consistent for some while. So the number of residential transactions is greatly influenced by the number of existing homeowners moving.

But why will they move less on average?

There’s the rub, the focus solely on the intergenerational unfairness and that young people are missing out on homeownership misses one important point. Older homeowners move much less than younger homeowners.

Let’s look at the stats and do some sums.

A quick analysis of the survey data on recent movers over recent history suggests you’re almost four times as likely to find a recent mover among householders under 45 years old than householders who are 45 and older.

Ok but why does this matter?

Compare 2000 with 2013. There were roughly the same number of homeowners in England and Wales. But on our figures (holding all other things than the age profile equal) the average likelihood of one moving was about 15% to 20% less in 2013 than in 2000.

This suggests a major source of residential transactions has shrunk fast (an underlying fall of about 10% in a decade) and was shrinking even as homeownership was rising.

From here the picture doesn’t get any brighter.

Low inflation will restrict house price rises, so the level of equity accumulation that promoted climbing the housing ladder among those in the generation now retiring may become a thing of the past. This suggests the propensity to move will be less among the young in the future.

Now I may be getting over concerned here, but my reading is that this (just one of a number of structural problems) will bear heavily down on transactions.

If that is so and the link between transactions and private house building remains stable we will, all other things equal, build fewer new private homes.

Talk all you like about demand being great and about a better planning system. The result would mean, as things stand, fewer homes built.