Relocating the value in land

Many of the nation’s most pressing and intractable problems, such as inequality, social mobility, housing shortages and ill health, stem from a failure to use and control land properly. That at least is one way to read the recently released, Labour Party commissioned report: Land For The Many [pdf].

These are big and important claims. However, the report seemed to provoke exasperation rather than engage interest in the media. Perhaps not a surprise. Many in the press interpreted the recommendations as a swipe at property-owning middle Englanders.

A recommendation that seemed to most incite some of the mainstream press was the idea of introducing a land value tax. This is interesting because land value taxation is common fodder for debate in housing circles and among its supporters one might include Winston Churchill and the non-partisan Institute of Fiscal Studies.

Leaving judgement on the recommendations aside, the report raises important issues, many of which tend to be overlooked in the increasingly regular stampedes to find a silver bullet solution to the housing crisis.

The report highlights the lack of transparency in the land market. It illustrates how land value is an escalating proportion of house prices. It also reminds the reader that: “The question of who gains the benefit from rising land values, and how this is used, has sat at the centre of land debates for centuries.”

Any report that takes a wide-ranging approach to complex issues such as those surrounding land, property and housing becomes an easy target for criticism over use of data, definitions and descriptions and missed opportunities.

One big missed opportunity was in not recognising just how important construction is in generating value. More later.

Anyway, here are some, hopefully, constructive criticisms.

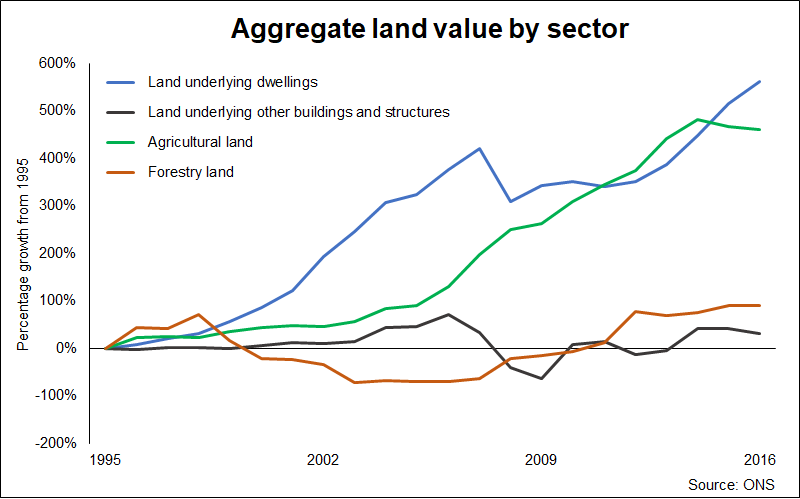

Turning to data. Focusing just on residential land values and Figure 1, which is the showpiece chart on page 20 of the report, there are concerns, not with the sources (they are from ONS sets used in National Accounts and Capital Stocks), but with the treatment.

Firstly, there are issues of aggregation and heterogeneity. The data used are for the UK. But in matters of land residential land value, London is hugely dominant. How much of the impact nationally is down to London? Without answering this we are left with lingering questions unanswered, such as is it a “global city” effect?

Secondly, and perhaps more problematic, is the time frame used. The data are taken from 1995, which admittedly were those provided by ONS to the report authors. When examining the rising land values underpinning the UK’s domestic stock, 20 years is short. It covers a period when the basic functioning of the housing market and housing delivery remained little changed, with most delivery through private house builders and the emphasis on home ownership.

Chart 1 recreates one using the same data presented in the report. It shows how the trend of rising residential and agricultural land prices has been extreme since the mid-1990s.

Chart 1 recreates one using the same data presented in the report. It shows how the trend of rising residential and agricultural land prices has been extreme since the mid-1990s.

But what about the wider context?

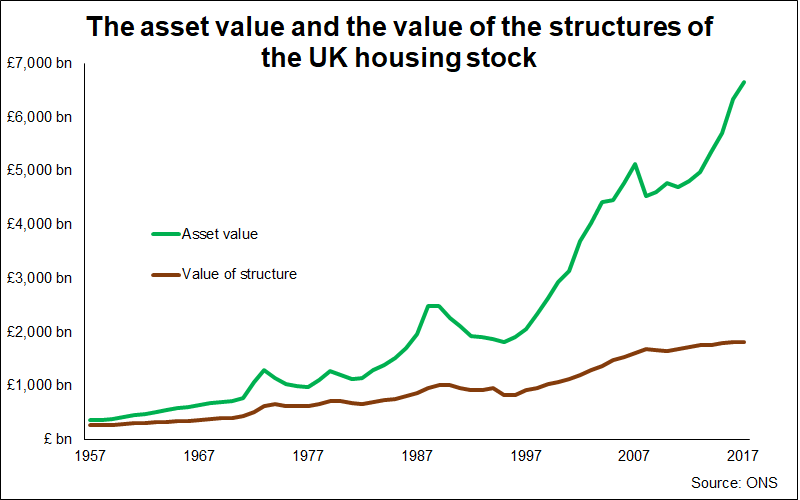

With help and some guidance from ONS, brickonomics in 2013 used similar data to look at the share of “land value” within the total asset value of UK housing. It showed a surge from the mid-1990s onward in the asset value of UK homes, as we see in Chart 2 (an updating of a chart produced in 2013). It shows house prices rising far faster than the value of the actual bricks and mortar (net capital stock).

It showed a surge from the mid-1990s onward in the asset value of UK homes, as we see in Chart 2 (an updating of a chart produced in 2013). It shows house prices rising far faster than the value of the actual bricks and mortar (net capital stock).

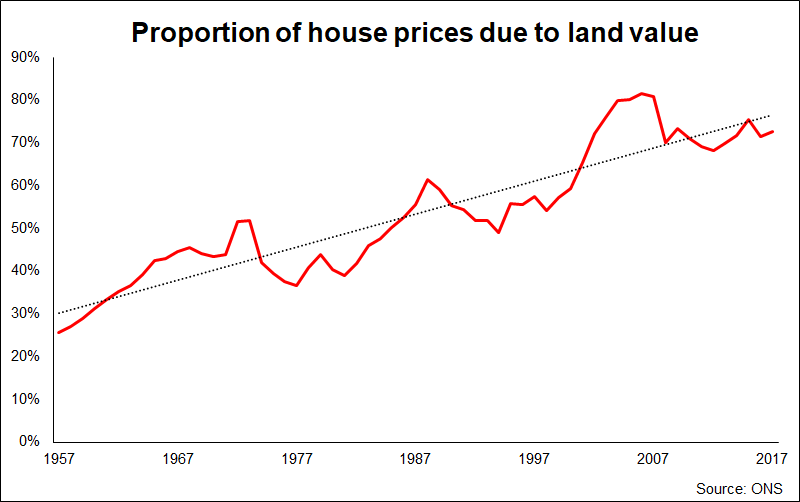

However, recasting the data we can see the share of land within the total value of the UK housing stock (Chart 3). The trend dates from the 1950s.

So, this isn’t a post 1990s phenomenon. It’s been going on for more than half a century. Indeed, the report references some impressive research from the report No Price Like Home: Global House Prices, 1870-2012 [pdf 3.5MB], that shows this trend kicked off in many developed nations around the 1950s. The steady growth which began in the 1950s, with bumps along the way, is an important point which should have been given more emphasis, particularly as the focus on the likely causes appeared to fall more heavily on more recent developments and policy changes. Clearly, numerous narratives might explain the phenomenon of house prices rising much faster than build costs. These might include any combination of factors ranging from changes in demographics, wealth, income, access to finance, social mobility, geographical mobility, taxation, legislation over tenancy and, of course, planning.

Clearly, numerous narratives might explain the phenomenon of house prices rising much faster than build costs. These might include any combination of factors ranging from changes in demographics, wealth, income, access to finance, social mobility, geographical mobility, taxation, legislation over tenancy and, of course, planning.

Why not chuck in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs for good measure? Has housing shifted from a basic physiological or safety need to a higher order need feeding self-esteem? Does this make housing a superior good, perhaps in some places even a Veblen good?

The key point is that to understanding which possible causes might be most pertinent we need to consider appropriate time frames.

This brings us to definitions, particularly what do we mean when we say land. Do we really mean access and rights to a given location, rather than the land itself? Is this a better way to look at things?

The distinction matters because they connote different things.

A quick look online reveals that for £1.2 million you can buy 4,000 acres of the beautiful Scottish Highlands. In the leafy suburbs of Surbiton, Surrey, £1.2 million buys a third of an acre. Location is what matters most in terms of value.

This I understood when, years ago, I owned a garden flat in London. The garden was as large as my flat. However, my flat was worth relatively little more than those above me with no access to outdoor space. Clearly it was having rights to live where we lived, rather than having control of actual land, which delivered most value. It was the location.

Despite “location” being a better descriptor, it comes up just three time in the report. This may seem like a petty gripe, but conceptually “location” helps us better understand the relationship of place (and hence land) to communities, to transport, to employment opportunities, to amenities and most other elements that together influence land value. It helps to separate more clearly between the built environment and the natural environment and how land comes by its vast value, mainly through the act of construction.

It also helps us appreciate why, when we tot up the total value of land below UK houses, the majority lies below homes that have stood for years. We need only look to Kensington & Chelsea in London to appreciate that.

The cost of land associated with the price of a new home is more likely to be nearer 25% than the 70% or more we might derive from the ONS data. Figures from Taylor Wimpey [pdf 1MB] and Persimmon [pdf 3.5MB] in 2018, show land was on average 15% to 16% of the sale value of their new homes. Even when we strip out profit and administration costs, land is about 22% of the direct costs of both the land and the build.

It is important to recognise the role of construction and its connection with people. The value of land under houses is realised initially through creating the built environment – the houses themselves and the schools, shops, roads, railways etc. that support them.

Subsequently, in concert with future construction, that value normally rises as communities mature and the activities and amenities that support them improve.

The value of the land at a given location tends to rise, with fluctuations, over decades and centuries as the things people want to be near to improve or become more desirable – note the price people have been prepared to pay to live near good schools in recent years – or as people move in and out of the location. Prices can clearly fall when the location becomes less attractive.

While location may be a better descriptor for analysis, the report is right to highlight the importance of land and who controls it. The report quite rightly points out the need for new development to “…be based on recognising communities’ goals, identifying suitable land to meet them, and ensuring sites are prepared with the necessary infrastructure.”

In that spirit we might add that the benefits of land value uplift should be distributed more fairly, particularly when publicly funded improvements to infrastructure provide huge windfalls for landowners.

Were this the case we might come to celebrate rather than fear rising land values. We might comfortably regard higher land values as an indicator of, rather than an inhibitor to, improvements being made to the built and natural environments.

This in turn might spark a far more productive debate about how construction creates value and how we might improve the vital symbiotic relationships construction has with people, the communities they form and the locations where these communities form.