What brick and block shortage? What house-building boom?

House building is enjoying its fastest growth for a decade or more and this is leading to shortages in the supply chain that threaten growth. That at least has become a widely accepted narrative that in many ways is characterising the current state of the construction industry.

But is this really the case?

The latest release by the business department BIS of the Monthly Bulletin of Building Materials and Components prompted me to scrutinise the data and various comments and question whether those two interlinked notions accurately reflect what’s really happening.

Certainly, you can find plenty of survey evidence and comment that seems to support the narrative.

Turn to the Markit/CIPS survey of construction firms and the message is clear.

In its last release of the UK Construction PMI David Noble, Chief Executive Officer at the Chartered Institute of Purchasing & Supply, said: “Housing activity growth was the highest in a decade and remains the fastest improving area of construction.”

Meanwhile Tim Moore, Senior Economist at Markit and author of the Markit/CIPS Construction PMI, said: “While input cost inflation eased in January, there were again signs that some suppliers are struggling to adjust to greater demand for construction materials.

“Vendor lead-times were lengthening even before the surge in construction output began last year, and now firms are reporting that cutbacks to capacity have caused supply bottlenecks as demand picks up across the sector.”

This seems to support the view of a boom in house building creating shortages in the supply chain. And we also find more support for this narrative in the latest RICS construction survey.

Within the 60 or so comments from surveyors recorded in the survey the word “shortage” pops up 10 times relating to both bricks and blocks and labour.

The release of this survey by the RICS and recent surveys from Markit/CIPS has fed into national news and trade press stories “revealing” that shortages of bricks, blocks and bricklayers are restraining growth in construction.

But my reading of the commentary written by the RICS economists suggests they are rather more circumspect on the subject of shortages than the media coverage might imply.

There’s good reason why the RICS economists would take a more circumspect view. They know full well that with surveys such as theirs or the Markit/CIPS there’s likely to be a range of statistical and cognitive biases at play.

That doesn’t mean the surveys are useless, far from it. They provide very useful indicators of change. But sound interpretation of the findings requires taking account of the broader context.

For instance, that 10 surveyors out of 60 or so mention shortages is important. But so is the fact that until recently they would have experienced extreme slack in the supply chain where the idea of shortages would have seemed ludicrous. This would be their reference point for filling in the survey.

It’s important to consider the base used as a benchmark for the responses and there’s a host of other factors that need to be considered if we are not to misinterpret the data from these kind of surveys.

Let’s look at other data sources that seek to measure actual amounts rather than observations made by respondents of perceived or even measured change.

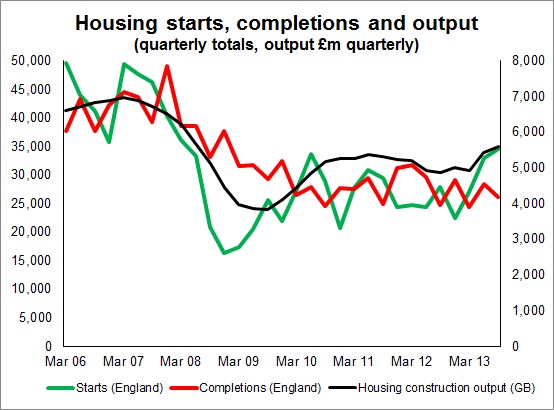

The first graph shows housing starts, completions and construction output up to September last year (note the starts and completions are for England only because data for other countries lags).

The first graph shows housing starts, completions and construction output up to September last year (note the starts and completions are for England only because data for other countries lags).

Sure there’s been a lift in housing output and starts have surged quite a bit. But looked at in the round there was equally fast if not faster growth in 2010. More importantly we see that the current level is still way off that seen before the recession.

The official data for starts and completions, however, don’t show what happened in the final months of 2013.

The output data, up to November, hint that the rate of growth was easing as the year headed to a close.

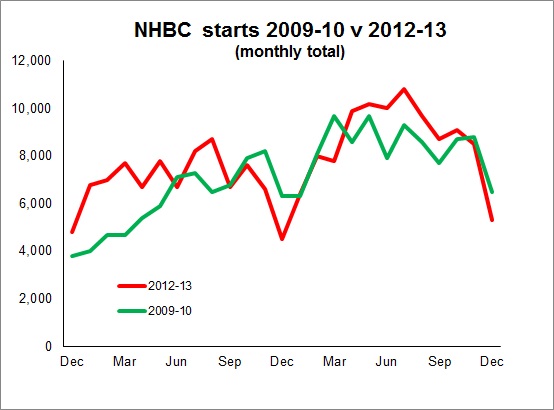

And we can get a suggestion of the direction of official housing starts from the NHBC starts figures. The graph shows monthly starts from 2009 to 2010 against 2012 to 2013. It’s clear that growth overall from 2009 to 2010 was greater than from 2012 to 2013.

And we can get a suggestion of the direction of official housing starts from the NHBC starts figures. The graph shows monthly starts from 2009 to 2010 against 2012 to 2013. It’s clear that growth overall from 2009 to 2010 was greater than from 2012 to 2013.

But as the graph also shows the surge in starts in the mid-year period of 2013 was more pronounced than in 2010. That surge faded faster than in 2010. This is important to note.

From this limited review of the data it seems the measures of actual outputs don’t, in a straightforwardly way, support the claim of “the fastest growth for a decade”.

This doesn’t mean that in the round house builders are not doing far better than in 2010. Of course they are. And as far as we can see there’s a much brighter future. But in strict terms output seems to have been growing faster in 2010 than now.

Let’s now turn to the shortages of bricks and blocks.

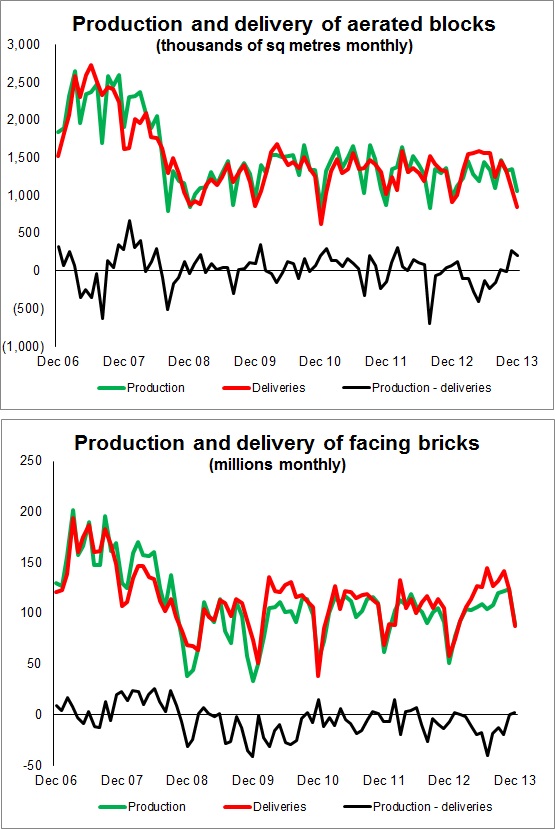

To keep the series fairly clean and try to avoid distortions caused by aggregation I picked facing bricks and aerated blocks. The two graphs show the production (green), the deliveries (red) and the balance (black).

To keep the series fairly clean and try to avoid distortions caused by aggregation I picked facing bricks and aerated blocks. The two graphs show the production (green), the deliveries (red) and the balance (black).

Yes there was a hard suck on the supply chain in the middle of 2013, but the imbalance of demand over supply for both facing bricks and aerated blocks wasn’t that special.

What’s more I’m told that overall production of aerated blocks was affected by an unplanned shutdown of one of the plants which restrained the normal early spring surge in production.

Looking at this data and room manufactures seem to have to flex production, there is no clear sign that capacity will constrain growth. Not yet anyway.

We can take a different look at the data and the context within which the industry is operating and develop a very different narrative.

Yes house building is on the up, although still a long way from pre-recession levels. But the massive surge in activity we saw in the mid-year of 2013 was heightened by a number of factors and is an exaggeration of the underlying growth rate.

So starts in the final quarter of 2012 were lower than in 2011, which illustrates the cautious mood in the market at the time. 2013 started modestly if not slowly for house builders, with the weather also hampering progress.

Prompted by easier credit, house builders reset their aspirations and wound up production, also in part to catch up from the slow start.

But crucially, not only did they raise activity to meet demand, they also had to restock their production pipeline to be able meet a much higher level of future production.

This inevitably created a surge in activity well above the growth in demand. This seems to have caught the suppliers, and most others, by surprise.

Meanwhile it seems manufacturers had, I am told, let their stocks dwindle. The data supports this view. Given the record of demand in recent years that seems a sensible policy. It seems they had relatively low expectations for 2013 and geared up accordingly. So when the surge hit they were not as prepared as they might have been.

In the case of aerated blocks, the loss of a plant made things worse.

Given this situation it is not surprising that there were shortages. Particularly as there will inevitably have been a degree of panic buying.

But it’s important to assess how this will have been perceived. Buyers will have adjusted their behaviour to fit a very slack supply chain. So it will have been a shock to find they couldn’t get what they wanted when they wanted it.

Hence the reaction and fears over shortages.

But the data, such as it is, doesn’t seem to support the notion of real shortages, other than those associated with a blip in demand. Yes imports have gone up, but they are still well below the level seen before the recession. Indeed they seem to be proportionate to the number of homes being built.

And by the end of the year we see production was outstripping deliveries.

It’s worth noting what the manufacturers themselves say. This is a comment from Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association, on the latest trade survey: “Importantly, manufacturers reported that, overall, capacity is not a significant issue and is unlikely to be during 2014 despite an expected rise in demand.”

The danger of overstating the problems of constraints in the supply chain is that we lower our sights. We need to build many more homes than we are.

Here’s a different take. Now I could well be totally wide of the mark, but…

We need to see house building continuing to expand at the rate it did in 2013, if not faster. I fear that its growth rate will ease as demand from the traditional private sector homeowner, which represents the bulk of new homes delivered, reaches a plateau.

This is the point at which the Government should consider how homes can be built outside and beyond the traditional private sector model in large numbers. It’s worth noting that output from the private sector in the UK has averaged less than 170,000 homes a year over the past 50 years.

If house building expands I do not see that the materials supply industry would not respond. Yes, imports may rise in the short term – that is the nature of things. But the supply will be there. And if there is a reasonable certainty over demand we may even see serious delivery through off-site manufacture.

The real focus for policy makers on constraints, opportunities, potential failures, crises, boon, however you want to see it, should lie elsewhere.

The attention of the construction narrative must shift firmly towards its people.

If the Government is serious about delivering more homes. If the Government is serious about moderating immigration. If the Government is serious about giving opportunities to our youth. Well if it is serious at all. It must embark on training a new generation of skilled construction workers.

More on that later…