Non-resi building sector could be hardest hit as house builders suck hard on the supply chain

The resurgence of house building has brought with it fears of a supply chain so stretched that we will see shortages appearing, production held back and costs rising.

There’s almost certainly something in this. It seems to be common currency. As I’ve discussed before, there are emerging problems with the supply of bricks and labour.

And EC Harris, for example, has picked up early signs that prices of materials associated with house building are rising faster than the average for all materials.

But it is early days and data on the effects are thin on the ground. Furthermore the construction industry is pretty flexible. If materials or skills are not available or too pricey, alternatives can be sought and designs and processes adapted.

So we can but speculate as to how severe are the pressures on the supply chain and what the consequences might be in terms of inflation or constraints on production.

However, what has interested me is that within this debate there seems to be one rather large omission – at least I haven’t really seen or heard it discussed. That is, with so much focus on house building and its struggles to cope with rising demand, little attention has been paid to the implications for the non-residential building sector.

In my view this sector is likely to be harder hit as house builders suck in resources from a shared pool. Why? Simply put, there’s more of a margin in house building, so potentially house builders have much more pulling power than do main contractors are still looking to win jobs on wafer thin margins, if any at all.

So what’s the situation?

All the data point to a strong increase in house building. Mortgage lending is up, transactions are rising and house prices are buoyant. This has provided an environment where house builders are talking about increasing production significantly.

There seems to be an urgency among house builders. Today’s market represents a sweet spot. Mortgage rates are low and mortgage lending expanded as a result of Funding for Lending. Help to Buy is attracting buyers. There is a backlog of desirous potential home owners. House prices are rising.

But this comfortable commercial environment could all change in a year or three. So there’s a sense of “fill your boots” while the going’s good.

To pick just one of the latest figures showing the scale of expansion, NHBC registrations of new homes were 25% higher in the first eight months of this year compared with the same period last year.

This rise does come from a low base, so we are not likely to see output reach pre-crash levels for some while.

But in the early stages of growth we should expect to see not just an expansion in demand on the supply base to meet the predicted extra sales of homes, but an additional expansion of demand as house builders increase the capacity within their production pipeline.

Furthermore if house builders decide to increase the proportion of flats in the expectation of growing demand from first-time buyers, this restocking effect will be greater. With flatted schemes more capital is locked up in the production pipeline for obvious reasons.

So we should expect the demands of the supply chain to be magnified in the early days of rapid growth.

Boiling all this down, the key point is that we should expect to see strains appearing in the supply chain, which long since adjusted to low levels of demand. These strains will be on materials, on labour and on specialist firms.

The good news for house builders is that much of their supply chain is potentially far greater than their total needs. They share it with the rest of construction. There are specialist areas, but for many of the trades there is significant overlap.

And the other good news for house builders is that they can decide what they want to build out on the basis of profitability. So if costs on a particular site look like rising too much, they can if they want hold fire.

But in truth on most sites house prices will be rising sufficiently to accommodate a level of bounce back in costs. Let’s not forget that house builders squeezed between 10% and 20% out of the build cost through the recession.

Now let’s look at the rest of the construction industry that shares a large slice of its supply chain with house building.

Many of the contracts up for grabs or that have recently been awarded will have been or still will be bid at wafer thin margins and probably with less contingency to accommodate risk than might normally be regarded as comfortable.

How easy will it be for contractors on these jobs to compete with labour and materials hungry house builders?

The answer is we don’t know. But one thing is for sure the chances are that main contractors looking to bid for non-residential work face a major new headache and greater uncertainty.

The pressure will not be even. It will come on some trades more than others depending on how stretched they already are and how much they are shared between the housing and non-housing sectors.

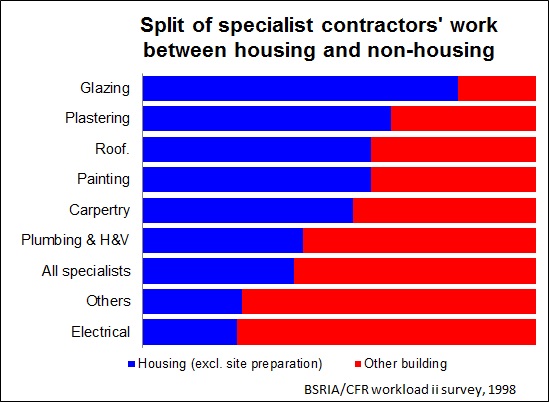

Knowledge of the overlap is pretty thin on the ground. But the extremely useful work done by BSRIA and CFR (now Experian) in their 1998 workload survey suggests that in some areas there may be a large overlap.

Knowledge of the overlap is pretty thin on the ground. But the extremely useful work done by BSRIA and CFR (now Experian) in their 1998 workload survey suggests that in some areas there may be a large overlap.

The graph shows the proportion of work undertaken by specialist contractors in housing and other building work. It suggests that a rapid expansion in the use by house builders of any of the top five, though perhaps less so glazing, could have a profound impact on the supply of skills available to the non-residential construction sector.

As I keep saying we are speculating. But there are big and uncomfortable unknowns. How much more risk will this mean for main contractors as they price for jobs? How many non-residential contracts might be lost if the supply of subcontractors dries up, or it prices rocket, or skills can’t be found?

It would be a profound irony if the expansion of house building led to a contraction in construction work elsewhere. And it would be an even more disconcerting irony if the taxpayer-funded assistance provided to house building prompted an increase in the cost to the taxpayer of public buildings.

As I have said many times before, we needn’t have been in such a mess.

But that’s the past. What we need now is to start thinking hard and acting quickly to avoid things getting messier.