Signs of recovery and the cost of missed opportunities in the housing market

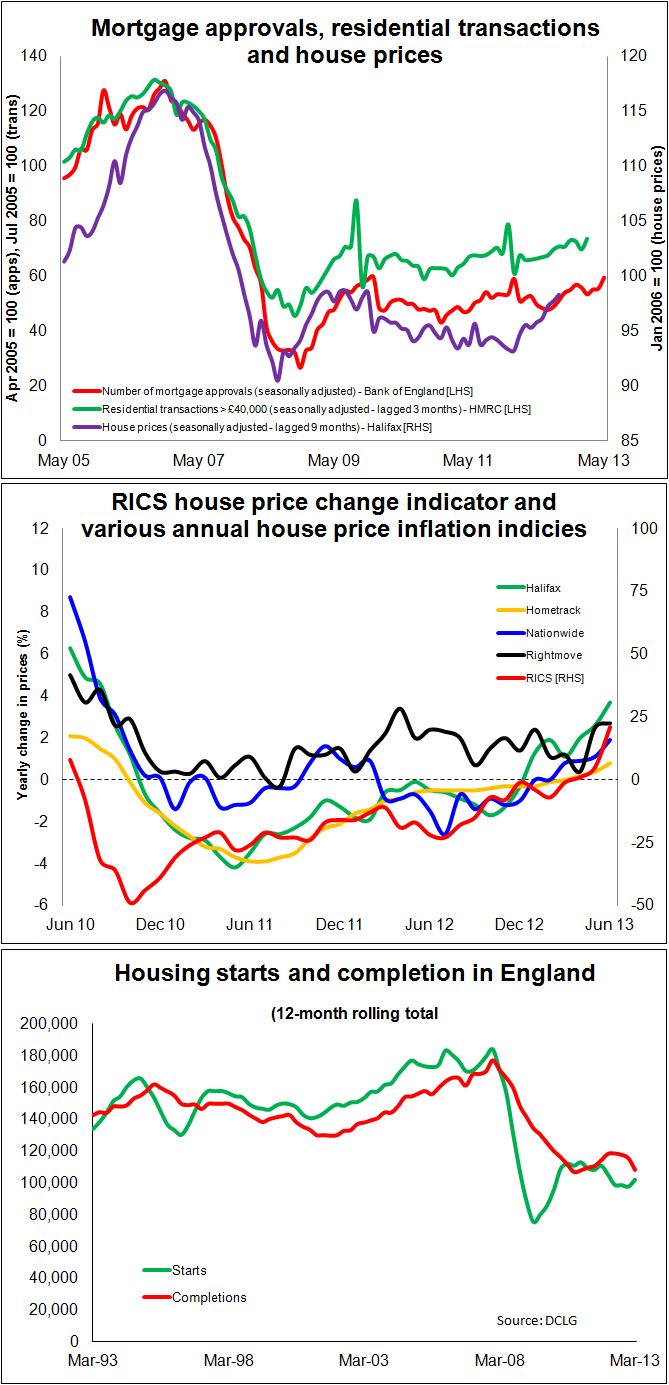

The latest housing market data all point to a recovery. Mortgage approvals measured over three months are at a three-year high. Prices are rising. Sales are more buoyant. Starts appear to be on the way up.

Indeed more positive wider economic news of late no doubt has helped underpin a sense of confidence, while the periodic scares from the Euro area seem to create less fear each time they come into focus and fade again.

The improved housing statistics should please the Chancellor. He did after all commit huge sums to boost home buying. So be prepared to see George Osborne pointing at housing statistics and delivering I-told-you-so statements.

He’ll be jollied too by an observation in the latest housing survey from the surveyors’ body RICS which says: “There has been a major turnaround at the regional level, with surveyors in seven out of ten regions in England and Wales recording rising prices, and in nine out of ten expecting prices to increase in the near term.”

He’ll be jollied too by an observation in the latest housing survey from the surveyors’ body RICS which says: “There has been a major turnaround at the regional level, with surveyors in seven out of ten regions in England and Wales recording rising prices, and in nine out of ten expecting prices to increase in the near term.”

That fits the all-in-it-together narrative rather nicely. Mind you RICS also points out in its latest housing survey: “The market is still very biased in favour of London and the South East, where price momentum is strong.”

However, pan out from the immediate data and things really aren’t all that rosy. They may appear splendid for house builders, but any suggestion that the Government is fixing Britain’s housing crisis would be well wide of the mark.

Look quickly at recent data and it is hard not to sense a recovery in the offing, with improvements in transactions, prices and mortgage approvals all feeding through and boosting house building. Starts, as measured by NHBC, were up particularly strongly in April and May.

But compare where we are now with where we were before the recession and the picture remains desperate. We’re not building enough homes. What’s more if you look behind the data you’ll see we’re bumping into a new set of potential problems as we expand production.

176,650 homes were built in England in 2007. At the time the Government felt we needed to be building well over 200,000 a year.

Last year we built 115,620. Rather shameful when we cast back to the bold statement in September 2010 by Grant Shapps, the Coalition Government minister who took over the reins at housing. He said it would be a failure not to build more homes than were being built before the recession. That was the gold standard, he said.

His analysis was wrong. His reliance then on Plan A – the New Homes Bonus and the community right to build – as the primary means to expand house building was wrong. It made little or no noticeable difference. Indeed reading the text of his promises to the Communities and Local Government Committee we can see just how poor analysis was.

His argument went: “…the more you wrote these 10 and 20 year plans through Regional Spatial Strategies, the fewer homes actually got delivered on the ground.”

It was a logical error to accept that there was a direct and singular causal link. He was wrong to think that planning was, to all intents and purposes, the root cause of lack of house building. It may have been a factor, but it was too simple to suggest it was the cause.

Leaving the niceties of logic and Mr Shapps’s failure to apply it to one side, we now face real problems caused by the failure to act quickly enough to build sufficient homes to sustain the house-building supply chain.

The market was always going to take a long time to correct to its former level. That was common knowledge. So it should be no surprise that we have had five years of house building either in decline or at a wretched level.

This has created a major problem. A long time in the doldrums has led to a rebasing of the supply chain. Capacity has been removed.

There’s little in the data yet to say that house building is running up against supply constraints, but there’s talk in the industry and the issue is mentioned in the media.

It may be that the shortages being felt by builders are temporary and down to surges caused by restocking or responding to a quiet first quarter. But with production at historically low levels and stocks tight any spurt in demand is more likely to stretch the supply chain.

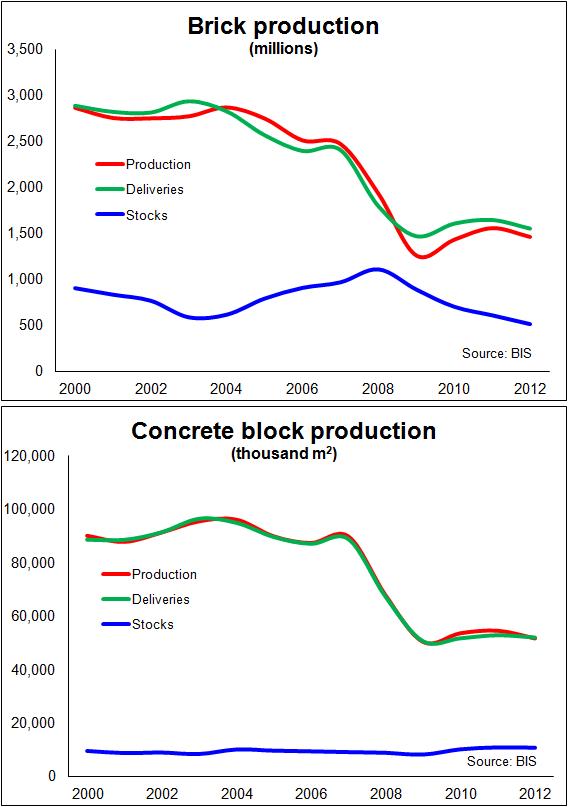

Let’s look at some supply data and see what it tells us. In the 12 months to May 1,418 million brick were produced. Production has been at that level for about five years. That is roughly half the level in the five years leading up to the recession.

Let’s look at some supply data and see what it tells us. In the 12 months to May 1,418 million brick were produced. Production has been at that level for about five years. That is roughly half the level in the five years leading up to the recession.

A similar pattern emerges if we look at concrete blocks and it will be the same across a whole range of products manufactured in the UK and used in house building.

Similarly the pool of available skilled construction labour has shrunk. There are fewer people in the industry than before and ever fewer in the “reserve army” of the unemployed. Many of those made redundant have either retired or are in other jobs and unlikely to return. Those who remain are getting older while little new blood enters the industry.

As Mr Shapps faffed about with planning rather than getting on directly funding building the housing shortage deepened unnecessarily. Ways could and should have been found to direct far more public resources to house building, the deficit reduction excuse is all too flimsy.

Now houses are more expensive than they need be and the market less stable. The housing benefit bill is larger. More people than need be live in poor housing. The list goes on.

In fairness to Mr Shapps the previous Government could have done more to promote house building. It did bring forward the public housing budget, but it too failed to respond with enough vigour. A mistake.

The construction industry and indeed the house builders within it are adaptive. The industry is flexible. But allowing its supply chain to dwindle to half its former size will have consequences, which could easily have been anticipated.

This will mean capacity constraints, especially if house building growth is strong, and rising prices. Ultimately the supply chain will respond. But the damage will be felt in other ways. For instance the Government’s wish to see more off-site manufacturing has been undermined. Why would a firm invest heavily in factory capacity and knowhow in a market that is so volatile?

It is also somewhat ironic that the recent construction industry strategy targeted the trade gap in building materials. A rapid assessment of the imports and exports of building materials generally associated with house building suggests that exports have suffered far more than imports comparing 2007 with 2012.

We can’t do much about the past. Opportunities were missed. So let’s hope this is a sustained recovery.

But lest we get too carried away it is worth remembering that whatever bounce back we are seeing comes after endless initiatives leading to the Help to Buy scheme, which has seen massive financial underpinning of incentives to boost private purchases, and in a context of ultra-low interest rates.

This support eventually will be removed.

Even if this recovery in the private sector housing market is the real deal, there’s still a long hard road to follow before house building is back on a track that meets the nation needs. This will require far more from the Government than props to private homebuyers on which it has so far relied.