Why young folk can’t buy homes

My patience runs thin when listening to the reasons why young folk can’t buy homes.

And today I’ve had to listen to and read various interpretations of why they can’t, prompted by the release of the interesting Halifax sponsored research “The Reality of Generation Rent: Perceptions of the first time buyer market”.

Call me unnecessarily reductive, but there is one simple over-riding reason why young folk struggle to buy a home, so simple it seems to be the most often overlooked.

Houses are currently very expensive relative to what people earn.

I have bumped into this particular elephant wandering about numerous rooms as I have listened to experts explain why our current generation of potential first-time buyers are struggling to get onto the property ladder. Strangely they omit to mention house prices, as if price has no bearing on a transaction.

Plainly, and the figures show, housing is more expensive now relative to people’s earnings than it has been for most of modern times with the exception of the crazy years of when lab-coated (my image) financial engineers were concocting a witches’ brew of a mortgage market.

And even that wholly unsustainable “here-have-more-money-than-you-could-possibly-need-and-a-bit-more” mortgage market failed to stop the decline of first-time buyers.

The rot set into that market in 2003, oddly enough after a whacking-great leap (almost a quarter) in house prices in 2002.

So could there be a link between actual house prices and the ability to buy?

Or were my parents just being perverse when they told me: “You can’t afford it because it’s too expensive.”

Maybe everything is and should be affordable if we can just find the right financial product with which to buy it.

Interestingly the Halifax survey found that 52% ranked high property prices within their top three “most significant barriers preventing people who would like to buy their first home from doing so”. It was ranked second on the problem list after the size of deposit.

More interestingly in the media reports I have so far read or heard and in the Halifax press release I have seen little if any mention of high property prices being the problem.

Indeed, the Halifax press release uses the word “process” seven times and the word “price” not at all.

You’d think there was a conspiracy if you were that way minded.

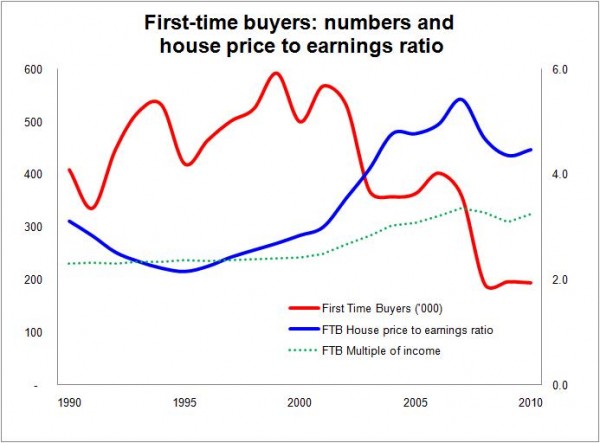

Anyway, let’s look at the graph. Here we see the number of first-time buyers, taken from Council of Mortgage Lenders figures and the Nationwide’s first-time buyer house-price-to-earnings ratio numbers.

Now you can query the figures this way and that, but let’s face it there does seem to be more than a vague coincidence that when the house-price-to-earnings ratio is high the number of first-time buyers is low.

It pretty well says: “High house prices mean low numbers of first-time buyers.”

Naturally there are a host of other factors and the efficacy of the mortgage process will be one. But to ignore house prices seems odd.

Now let’s take a step back. Is the problem with the post-credit-crunch housing market really all or mostly about first-time buyers?

If you can be bothered to delve into the morass of data on mortgages you find that the share of first-time buyers in the mortgage market has if anything increased since the credit crunch.

Relative to mortgages for home movers the proportion of mortgage loans for house purchase for first-time buyers was higher in the three years after the credit crunch than in the three years before. In part this may be down to the various policies aimed at encouraging first-time buyers into the market.

Now, you may argue this is a false argument because, perhaps, people are now happier to stay longer in their newly bought homes. But I doubt that their has been that cultural shift.

The reality is that liquidity in the market as a whole is much reduced. Worryingly that is probably very bad news for building private sector new homes, as I have illustrated before. And as we are resting on private sector building to deliver new homes that is a problem for housing supply.

Indeed a more disturbing reality is that rather than willingly choosing not to move, home owners are increasingly financially constrained from moving. I have argued many times before, once on the housing ladder new owners find the rungs above far hard to reach than before, so they are in effect trapped in their homes for longer.

Meanwhile, there is a knee-jerk response to falling numbers of first-time buyers with calls to make it easier for them to borrow, as if this will solve the problem. But as the graph shows even chucking money at the market with wilfully weak controls did not stop the numbers falling.

Moreover, by crowbarring more first-time buyers into the market we risk creating a sclerosis in the market with an increasing proportion of home owners unable to move on.

The hard truth is that homes are expensive today and unless they get relatively cheaper we will have a dysfunctional market or will have to accept a different structure of tenure. In the case of the latter that will mean creating more renting and more appropriate forms of renting.

It is interesting to note as an antidote to what many policy makers are suggesting for the solution to Britain’s housing problems the comments made by the think tank IPPR with the release of its report: “Forever Blowing Bubbles? Housing’s role in the UK economy”.

IPPR Director Nick Pearce says: ‘We must learn the lessons from this economic history. A central plank of economic policy should be to target moderate increases in house prices, rather than allowing runaway house price inflation which is always damaging in the long run.

‘The Housing Minister, Grant Shapps, has tentatively floated the idea of aiming for house price stability but he and George Osborne should go further and make it an explicit policy objective. We need tougher mortgage market regulation from the FSA, especially caps on ‘loan-to-value’ and ‘loan-to-income’ ratios.

‘The UK has the lowest level of institutional investment in private rented housing in Europe. We should be encouraging institutional investors to ‘build-to-let’ while discouraging individual property speculators using buy-to-let mortgages which can artificially inflate our housing market.’

Whatever the policy direction, it must be based on a realistic understanding of the facts, not some popularised interpretation of the housing crisis and a daft but prevalent belief that however expensive houses get they can be afforded by the masses if the right mortgage package is available.

3 thoughts on “Why young folk can’t buy homes”

Brian,

Brickonomics is billed as delivering no nonsense analysis, and so it is with this piece. Well said. As to why few others preach that message: hush, hush. You are delivering the truth, and that often hurts.

Meanwhile, I wonder what your thoughts are concerning changing attitudes towards saving? Most of those who bought when I was young lived relatively lean lives while saving, often for three years, and to accumulate a 20-25% deposit. I wonder if today’s potential first-time buyers are prepared to endure that process, especially given endless consumption possibilities.

Martin Hewes

Hewes & Associates

Martin,

You asked about my thoughts on changing attitudes to savings. I am happy to give some observations, but I can’t claimed to have looked at the numbers in detail.

The first point I would make is one of context. I believe, and have done for the best part of a decade, that institutionally we have not adjusted to a low inflationary environment and consequently lower interest rate environment. This has a profound impact on the mathematics of buying a house with a mortgage. In brief, as you will know, it means immediate affordability looks more attractive – monthly payments are lower. But in response prices rise for later entrants to the market. The sting is that wage inflation, which is lower in a low inflationary environment, is less effective in reducing the relative value of the sum borrowed. This means the borrowed sum is a heavier burden in the later stages of the mortgage period than it would have been.

This is important because the emphasis when potential first time buyers are looking at affordability is to consider the burden on finances now (can we afford it?), rather than the burden in five or ten years time.

The low inflationary, and consequently lower interest rate, economy we have seen for most of the past two decades removed one of the controls on house price inflation. Little wonder that we saw such growth in house prices. For much of the earlier period of “mass” house buying past there were controls on credit. And through the 1970s and 1980s, when mortgage lending became steadily easier, there was relatively high inflation and high interest rates. In the 1990s and 2000s neither of these inhibitors were in place.

So let’s consider the response to the potential first-time buyer when house prices are rising and mortgage lenders are prepared to give you a 110% mortgage. Why would a rational person save unless they feared an imminent house price collapse? To wait to enter a rising market would be to burden yourself with increased costs. The simple mathematics of the housing market in the years up to the credit-crunch were heavily weighted against saving and towards debt – by circumstance and design.

As to the broader issue of a changing culture towards borrowing and saving. It will be interesting to see how over time the “student loan” generation reflect on the burden of debt, especially if we move to a higher interest rate environment. If debt becomes associated with “burden” rather than “liberation” then I suspect there will be a shift in the culture of borrowing and saving.

Attitudes can change rather rapidly. I recall in late 1986, as the market boomed, being told you’re mad not to buy a house. In late 1995, after years of house price falls, I was told you’re mad to buy a house. I bought in 1986 and it turned out to be ill-advised. I returned to renting. I bought in 1995 and it produced almost criminal gains in capital appreciation.

The mortgage industry should be taken to task for allowing excessive borrowing in the first place – had it not been permitted, this issue would likely not exist – instead it continues to perpetuate with more and more hype from the the banks pumping buy to let and the media only reporting what will gain the most readers.

Comments are closed.