Has the Office for Budget Responsibility screwed up the Stamp Duty figures?

I appreciate that Office for Budget Responsibility is taking flak at the moment for being “optimistic with the truth”, but I can’t help but chip in with yet another gripe.

I have deep concern that it has made a huge fluff of the numbers for Stamp Duty Land Tax that could leave the Treasury billions short on its target for the revenue so much needed to close the deficit.

We are being asked to believe that by 2014 the Treasury will be taking more in real terms from tax on the sales of residential and commercial land and property than it was during the pre-credit crunch boom years.

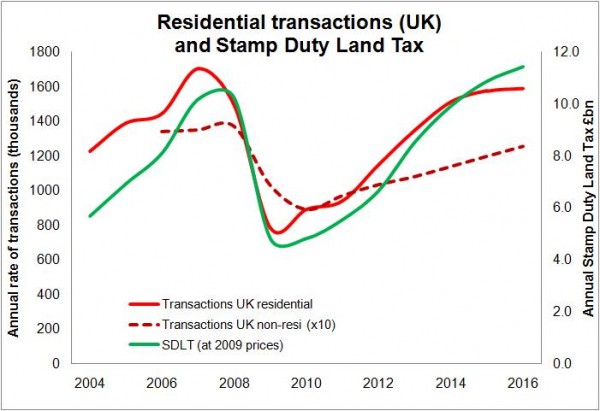

The graph shows the level of Stamp Duty taken from both commercial and housing property sales corrected for inflation (using OBR and Treasury deflators), the level of residential transactions and non-residential transactions magnified by 10 (to get it on the graph). The data coming from HMRC with the forecast to 2016 taken from OBR figures.

The graph shows the level of Stamp Duty taken from both commercial and housing property sales corrected for inflation (using OBR and Treasury deflators), the level of residential transactions and non-residential transactions magnified by 10 (to get it on the graph). The data coming from HMRC with the forecast to 2016 taken from OBR figures.

At the height of the boom HM Revenue was taking in cash terms just shy of £10 billion in SDLT, mostly from home sales, which provided about 2.2% of HMRC’s take.

That tax take dropped to £4.8 billion in 2008/09, which amounted to about 1.1% of HMRC income.

What is clear, and indeed unsurprising, is how volatile this tax is. It takes heavily in buoyant years and lightly when the property market slumps.

Now, looking at what the OBR expects will be taken from this tax in coming years is interesting. It expects that in the financial year ending 2015/16 SDLT will take in £13.5 billion, or about 2.5% of HMRC revenue.

By 2014 it expects to be taking in more than £12 billion annually, which when inflation is taken into account is a bit more than what was being taken in 2007.

Yes, there have been tweaks to the thresholds and any inflation in prices would bring a higher proportion of transactions into scope.

But I am not alone in thinking that the figures produced by OBR seem exceptionally high with an extreme downside risk. “Preposterous,” was one word use to describe the forecast by one of the industry experts I chatted to on the subject.

The trouble is that if OBR has this wrong it may prove serious, not just for the UK economy generally, but for construction. Because a major shortfall in tax of that scale will, almost certainly, have the Chancellor reviewing his position on capital spending.

It does not seem unreasonable to suggest that we could be talking about a tax black hole of anything up to £4 billion.

So why might OBR have it wrong?

Firstly there is an assumption that the number of transactions will bounce back more or less to the levels we saw during the boom.

Firstly there is an assumption that the number of transactions will bounce back more or less to the levels we saw during the boom.

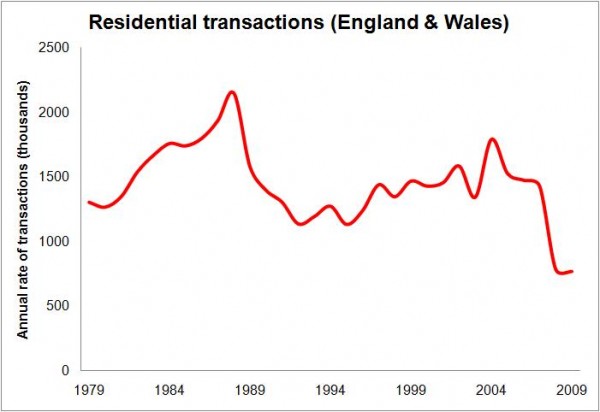

Historically this looks unlikely, if we look at the graph of transactions since 1979 (this is one I had prepared before and it is just for England and Wales, but will do for the illustration).

It shows how long it took for transactions to recover after the previous collapse in the market. Admitted history is not necessarily a clear guide to the future, but is still tells a story.

But this bounce back within the OBR forecast, my more econometrically-minded friends suggest, looks like a “revert to mean” problem within the model being used, rather than a considered judgement of what is likely to happen given the prevailing economic forces at work within the housing market.

Leaving aside historical precedent, there is currently a huge number of drags on the level of transactions, which suggest that a bounce back in home sales is very unlikely.

There is a chronic affordability problem. This is not the background to a surge in transactions. And the assumptions that OBR makes about the level of wage growth and the level of house prices does not point to an improvement in affordability.

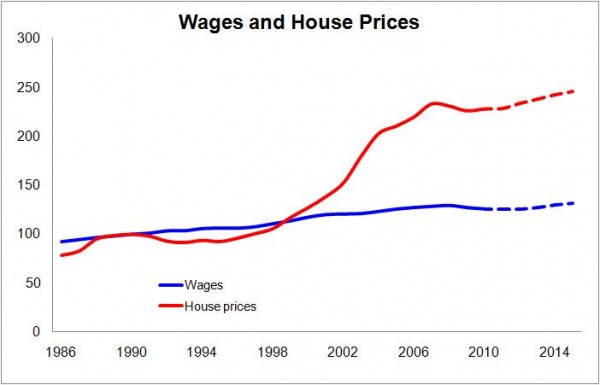

The crude wages-house price graph (right) clearly shows a step change in the value of homes to the wages being earned by would-be buyers, with the recession not really providing a full correction in affordability.

The crude wages-house price graph (right) clearly shows a step change in the value of homes to the wages being earned by would-be buyers, with the recession not really providing a full correction in affordability.

You can do numerous graphs to show that the level of house prices to earnings remains exceptional, this graph simply takes nominal average earnings (figures from measuringworth.com) and CLG house prices with forecast growth figures from OBR. Deflators were then applied to adjust for inflation.

I personally would be quite sceptical about the forecasts for house price growth, but we will leave that to one side and take them as given.

Yet, while the assumed increase in house prices will technically raise more funds, higher house prices will bear down on the rate of transactions and most likely reduce the overall tax take.

It could be argued that a continuation of low mortgage rates might appear to be a solution here. But as I have argued before a long spell of low interest rates rebases house prices to a higher level and reduces the ability of first time buyers to trade up.

I have estimated before that, given the prevailing mortgage rates and house prices, all other things being broadly equal, it will take a first time buyers about twice as long to build enough equity to shift up to a second home as it would have done in the 1980s.

This slow pace of trading up will continue to bear down heavily on the level of transactions.

However, probably the clinching argument is that we are, in all probability, entering a new era of mortgage funding very different to the recent past.

The availability of funds will be significantly tighter than in the past as lenders build the capital bases and seek to fill the looming funding gap. This must restrict the numbers of first time buyers entering the market. This will restrain the number of sales.

Yes, a rapid increase in commercial property sales could help to rebuild SDLT, but this is similarly constrained with finance less available than in the past.

I just hope Sir Alan Budd and his team know something I don’t, otherwise the squeeze is set to get tighter.