Is George’s housing prescription simply a marvelous medicine to boost home ownership?

Much excitement ahead of the Autumn Statement focused on how the Chancellor planned to tackle the housing crisis?

Quite right. Housing has been steadily rising up the premier league of political concerns.

Almost everyone agrees there’s a crisis. But turn your head this way or that and you’ll find a lobby group, angry mob, or a concerned person defining the housing crisis differently.

So what is the housing crisis exactly?

Is it:

- Homelessness?

- Awful housing conditions for too many?

- Poorly allocated housing (under occupancy and overcrowding both rising)?

- Too many hardworking families unable to afford a decent home?

- Polarisation in access to housing threatening social mobility and social cohesion?

- Home ownership falling?

- Ever more people locked out of home ownership?

- Disruptive intergenerational housing inequalities?

- Not enough homes being built?

- Too few people to build houses?

- Planning blocking necessary house building?

- Ludicrously high house prices?

- Mortgage debt threating the nation’s financial stability?

- A housing market that restricts labour mobility?

The list could go on. You could certainly add immigration into the mix.

But why bother asking what exactly it is, if we all agree there’s a housing crisis?

Because it’s too easy to bundle all the problems together and conflate them into the single notion of a “housing crisis”. Too often the solution is reduced to a simple single particular remedy – the silver bullet – normally weighted to fix the particular aspect of the crisis most pressing in the mind of whoever suggests the remedy.

So we regularly hear that the solution to the housing crisis is to: relax planning, build on the green belt, provide mortgage guarantees, subsidise first-time-buyer deposits, scrap stamp duty, levy a land value tax, build more council houses, tax the rich and so on.

In reality selecting an appropriate policy prescription to solve these interconnected but equally distinct problems is tough. Some policies may improve some problems but make others worse. Furthermore short-term fixes may have nasty long-term effects. Equally long-term fixes might have nasty short-term effects.

It’s all a bit complicated. (Useful reading from Michael Edwards)

One thing we know. Over the past 10 to 15 years, as housing has steadily crept up the political agenda, we’ve seen many strategies, a host of policies and witnessed huge sums of public cash invested in supposed solutions. Each strategy comes with implicit or explicit promises of fixes to the crisis. The phrase “radical and unashamedly ambitious” from 2011 springs to mind.

Judged against almost any measure on the list above, these have failed. If only on the grounds that more people now seem to accept we have a housing crisis.

To date most policy has tended to frame the housing crisis broadly in terms of a lack of supply of housing, with various broad targets in mind, all far greater than we currently build.

So it is interesting to see the Chancellor choosing to express the crisis differently. In his eyes the crisis is one of home ownership.

Does this matter?

Well, yes, because it will shape the choice of policies prescribed to tackle the housing crisis.

Naturally, house building (and the supply of housing) remains very important. But in a political sense it becomes secondary to home ownership – a means to an end. Though, it must be said, championing house building also has the political by-product of providing photo opportunities to wear hi-viz jackets and talk about being a “builder”. And the Chancellor must be acutely aware of the risk of being politically skinned alive if by 2020 the nation is still delivering far fewer homes a year than before the recession.

The primacy of home ownership has been evident since the election, but in his Autumn Statement speech he spelled it out very clearly: “Above all, we choose to build the homes that people can buy. For there is a growing crisis of home ownership in our country.”

This is very different to saying we must build homes because we need more homes to live in.

Later he added: “Frankly, people buying a home to let should not be squeezing out families who can’t afford a home to buy.” This underpinned his case for raising stamp duty for buy-to-let homes.

The overt shift that placed home ownership central has come with a Conservative majority able to form a government on its own. Interestingly, whether in response or independently, the opposition appears also to be placing greater emphasis on home ownership, with shadow minister for housing, John Healey, commissioning Taylor Wimpey chief executive Pete Redfern to produce a report on the decline.

Certainly driving ownership was key to the Chancellor’s July Budget when he chose to restrict tax relief for buy-to-let landlords.

Clearly he is prepared to hit those who might be considered within his natural electoral base – buy-to-let and second-home owners. They may feel betrayed, as in their eyes, especially those who buy new-build homes, they are providing a service (rented homes) and (for those who are new-build investors) helping to fund the building of new homes.

Meanwhile looked at from a purely house-building perspective it could be argued that making buy-to-let investment less attractive will harm the viability of some housing developments, especially city-centre blocks of flats where investors buying off-plan help to reduce risk.

This suggests that the Chancellor is willing, when he sees reason, to put home ownership ahead of serving his expected electoral base and ahead of house building. So it is totally consistent with his position if he believes buy-to-let landlords are snapping up homes at the expense of home owners.

In reality, the political and construction impacts are probably more muted than they seem on the surface.

The Chancellor has made plain his desire to win a greater share of the “blue-collar vote” from Labour, so squeezing his natural electoral base to give more room for “strivers” with lower incomes is consistent with his broader long-term political plan. Furthermore when it comes to building for rent, the Chancellor will be looking to push institutional investors working at scale.

Note too, from the Office for Budget Responsibility analysis (Graph 1), that the Chancellor is willing to slow the housing delivery from housing associations, at least in the short term, in his pursuit to boost home-ownership rates.

Note too, from the Office for Budget Responsibility analysis (Graph 1), that the Chancellor is willing to slow the housing delivery from housing associations, at least in the short term, in his pursuit to boost home-ownership rates.

This illustrates the point that understanding what is defined as the “housing crisis” is vital to understanding the policy approach. It also shapes the challenge the Chancellor has set himself.

Whether you agree or disagree with the focus on ownership as the problem, there is a strong case for having a clear definition. It provides a focus for policy. But, then again, if you define the crisis so narrowly, there is a danger that other aspects of what falls within most people’s interpretation of the housing crisis are made worse.

Let’s however briefly examine the “crisis in home ownership” and what might be the effect and effectiveness of trying to solve this particular problem, asking four questions.

Firstly, what is the crisis of home ownership?

Fortunately for me, Neal Hudson at Savills produced a very useful note in July on this very topic.

But here are a few statistics and comments I might add that I think are important.

Estimating from the limited data available from the Survey of English Housing (SHE) and its successor the English Housing Survey (EHS) and with reference to CML’s research on first time buyers, the decline in home ownership appears to have begun just before or just after 1990. Yes, at a headline aggregate level the proportion of home owners continued to rise into the early 2000s, but the proportion of young home owners dropped dramatically. There are many and complex reasons for this, but the seeds of falling headline home-ownership rates were sown then.

The continued growth in the overall proportion of home ownership was propelled by generations of older mainly renters being displaced by the next generation who were more likely to be home owners. Growth in the overall home-ownership rate was also buoyed by successive waves of pensioners being more likely to own their homes and to live longer than their predecessors. And of course there was the Right to Buy.

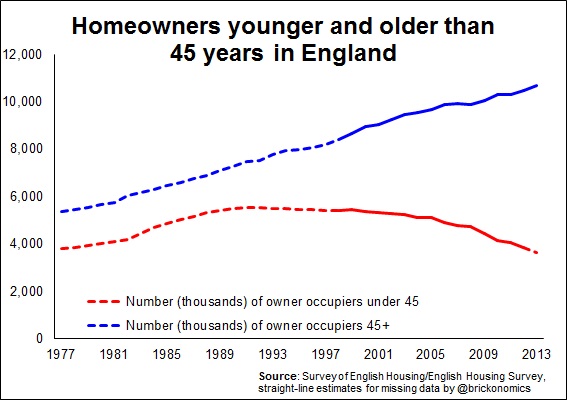

Statistics from the SHE and EHS show that in 1977 46% of those aged over 75 owned their homes. Today the proportion is about 77%. In 1977 more than 58% of householders under 45 years old owned their homes, in 1988 the proportion was 68%. Today the proportion is below 45%. Graph 2 shows the change in home-owner numbers aged above and below 45 years old.

Effectively a wave of home ownership passed through the system and is now crashing on the shores, leaving in its wake a trough of low levels of owner occupiers. It is this trough that has steadily dragged down home ownership rates over the past 10 years or so.

Effectively a wave of home ownership passed through the system and is now crashing on the shores, leaving in its wake a trough of low levels of owner occupiers. It is this trough that has steadily dragged down home ownership rates over the past 10 years or so.

It is very important to note that the crisis of home ownership, if you see that as the housing crisis, started in the 1990s, not with the Great Recession.

If Osborne wishes to create a nation where owner occupation is the norm, it would be wise for him to examine what has eroded home ownership for the young in the years that followed the late 1980s boom. I suspect the answer is not simple. But noting the near simultaneous boom in house prices from the late 1970s across many nations might be a good place to start.

Secondly, what is the Chancellor’s aspiration, his target if you like?

I can’t seem to find a simple number or scale against which to judge his efforts. However I am once again indebted to a tweet from Neal Hudson of Savills. At a recent housing seminar hosted by Savills, Melanie Dawes, Permanent Secretary for DCLG, said her department was targeting 1 million new homes and 1 million new home owners by 2020.

This is ambiguous. But given that the number of first-time-buyer loans made in 2014 topped 300,000 we must assume these are extra. Certainly, if I were sat on the opposition benches, I’d be keen to quiz the Chancellor more on the detail of his targets for house building and home ownership and his reasoning for placing ownership central to his housing policy.

Thirdly, is the target achievable?

Because the target appears to be expressed as a number rather than a percentage, population growth will do some of the work.

In terms of the headline percentage figure for home ownership (the one that gets followed), the task appears harder. One force driving home ownership rates up has been ageing home owners displacing older non-home owners. This effect has pretty much run its course. The effect of falling numbers of younger home owners from the 1990s onwards will be feeding through into the upper age brackets and may well erode the currently high rate of home ownership among the retired.

Right to Buy and expanding shared ownership may assist Osborne in his ambitions, raising rates across the age profiles. But in general the flows into and out of home ownership are extremely hard to gauge with any accuracy. Given historically very low levels of ownership among the young, it does seem that declining home ownership at an aggregate level is baked into the data, as a generational trough in home ownership displaces older home owners, reversing the previous trend.

Fourthly, what might be the implications of pursuing a housing policy focused on home ownership?

This is a huge question. I’ll restrict myself to a few observations that may be worth noting.

On the value of high levels of home ownership there are things to be said either side. On the plus side, widening access can potentially distribute wealth and provide financial security for many. It can also incentivise community engagement. On the negative side, it can engender nymbism. It has been found to negatively correlate with labour mobility and the leverage effects can put some unlucky households at high financial risk with some ending up with negative equity. So, while home ownership has many benefits for individuals, society and the economy, it also has drawbacks.

With regard to pursuing a policy highly focused on home ownership, it seems to me very important to look at periods when home ownership has expanded. Naturally Osborne’s mind will gravitate to the Thatcher era. But that period merely built on a pre-existing surge in home ownership post War, which in many ways was built on the expansion of home ownership in the 1930s.

Notably, there is a big difference between those periods and now in that acceleration in home ownership occurred then when prices of houses and land were relatively much lower relative to incomes than they are today.

Many factors influence house prices. Housing supply, interest rates, access to finance, wealth effects delivered by rising or falling prices, regulatory constraints, economic cycles, population growth and migration and income distribution to mention but a few.

But a pertinent question to consider is how easy it is to accelerate home ownership rates when prices are high and what are the potential associated risks and benefits.

Before that it might also be worth considering the role home ownership itself may play in price growth.

Graph 3 compares Spain and the UK, where home ownership is high with Germany and Switzerland where home ownership is much lower. It is not meant to be presented as cast-iron proof, but the data strongly suggest that higher home ownership makes for faster rising prices. I selected Spain because here there can be no question about slackness in house building being the cause of rising prices. If anything over-building was an issue in the run up to the Spanish housing crash.

Graph 3 compares Spain and the UK, where home ownership is high with Germany and Switzerland where home ownership is much lower. It is not meant to be presented as cast-iron proof, but the data strongly suggest that higher home ownership makes for faster rising prices. I selected Spain because here there can be no question about slackness in house building being the cause of rising prices. If anything over-building was an issue in the run up to the Spanish housing crash.

It certainly makes a strong case for asking whether increasing home ownership creates faster house price growth and then in turn acts as a break to new entrants. If this is so, policy prescriptions should be seen and adopted in this light.

In “normal” circumstances broadly four things mostly influence access to the housing market. So, relative to earnings and wealth: How expensive are homes? How much of a deposit is needed? How high are mortgage rates and can the payments be serviced? Also, how easy is it to get a mortgage?

Currently house prices are high and mortgage rates low. Servicing debt is not overly problematic, unless interest rates rise. But with high house prices saving for a deposit has become increasingly tricky.

So mainly to address this issue we have seen a fifth factor increasingly come into play. Can another person, the bank of mum and dad or the Government help fund access to home ownership?

This is where the government has been forced to look for solutions. The flagship scheme, Help to Buy, directly addresses this issue.

There are many reasons why you might wish to support a given market. And the housing market is critical to the nation’s welfare. But experience tells us when you mess with a market you risk messing it up. Furthermore, the longer you interfere to support a market the harder it is to withdraw that support. Other elements of the market adjust to create a new normal.

Interfering in a market has consequences. That’s the very reason to interfere. One concern with Help to Buy is its potential side effect of raising house prices by increasing demand. If it does this, in the long run its very purpose is undermined. In extreme circumstances and in the short term this may be acceptable if it is needed to kick start normal activity. The danger is it becomes a permanent feature.

Compressing all the above and seeking to draw conclusions my first thought is that the Chancellor will struggle to raise rates of home ownership.

To make any dent in the downward rate of home ownership, his policies will have to raise dramatically access by young people into the market. This process will be made harder by other factors discouraging rising home ownership. Historically high income inequality makes it harder to include those lower down the income scale, and harder still if house prices are running historically high. The flight of the increasingly debt-burdened young into cities where both demand and prices are high makes the job even tougher. Many may choose to delay entry into owner occupation.

More worrying to me is what might be the effects of force feeding first-time buyers, however politically and (in the short term) economically attractive that might seem. It would be folly to forget that the roots of the Great Recession are most often tracked back to sub-prime mortgages that sought to pump up home ownership among those on low incomes unable to sustain the cost.

While using state funding to pump up home ownership may be superficially very attractive to some, it looks also to be courting risk.

I can see there is a temptation for private house builders to lap it up with glee. The immediate impact on their share price rather suggests their investors see huge financial benefits. So who am I to challenge that view?

However, as mentioned at the outset, policies can have very pleasing short-term impacts, but carry nasty long-term effects. The analogy with drugs is hard to resist here.

There is a danger that the “drugs” Osborne will prescribe to boost performance will develop into a dependency. Worse, if taken over the long term they may well have other nasty side effects, making the underlying problems worse or creating new problems.

Ultimately, the best solution and at the root of the expansion in home ownership in the past was the relative cost of homes to incomes.

Yes, you can cheat the monthly burden of home buying with ultra-low interest rates, but we are there already. Will mortgage rates stay this low for decades? You can provide subsidies. But are potential home owners to be offered state aid indefinitely?

Ultimately, as with most essential goods, if you want more people to buy them you make them cheaper.

Over the long term, assuming we are not wedded to ultra-low interest rates for decades, if homes are to become more affordable they have to become cheaper relative to incomes. That will create a much firmer foundation on which to build rising home ownership – if that is what the nation really wants.

This suggests that the policies we need if we are serious about spreading home ownership across the population and more evenly through the generations are those that, over the long term, hold prices more stable and lower relative to incomes than they are today.

This was widely recognised five years ago, and was a view taken by the housing minister of the day, Grant Shapps. But it has been conveniently dropped. Why? Well, a quote from the much-lauded economist Keynes may offer some insight: In the long-term we’re all dead.

Perhaps to understand why the housing crisis is now being framed as a crisis of home ownership we should not seek answers in George Osborne’s long-term economic plan and pay more attention to his long-term political plan: Prime Minister?

He is frequently described as a political Chancellor. He’ll be well aware of the surveys finding that home owners are about twice as likely to vote Conservative as Labour.