How old is the average construction worker?

A figure keeps cropping up that suggests the average age of a construction worker is in the 50s and the industry is getting older by the day.

That makes for a good scare story. But is it true?

The story came up again in a construction economics meeting I was at last week. One anecdote suggested the faces on site looked 10 years older than 10 years ago.

Could this be real, the effects of recession-related stress on hard-working construction folk making them look older, or perhaps a cognitive bias (for instance a form of recognition bias where we notice and remember people of our own type more than others)?

Let’s not forget also that the population is aging generally, so you might expect an industry to reflect this.

So what is the answer?

It’s not all that easy, because industries and occupations change and are reclassified so the data are not always that easily compared. Also not all construction trades work in construction and not all people that work in construction work on sites.

We can get construction-related occupations from the census. For simplicity I took “skilled construction and building trades” for 2001 and 2011.

I also happened to be in the British Library last week and hurriedly checked the 1951 census. I only had time to take the numbers by age for males categorised as “workers in building and contracting” and “painters and decorators”. This should provide a reasonable sample for illustrating the spread of ages within construction, although you might rightly argue that it may be biased towards younger people because the specification of skilled isn’t there and female workers were ignored.

I fiddled a bit with the age bands making simple assumptions to reallocate people to fit a consistent set of age bands for the three periods. This will not have made much difference to the general shape.

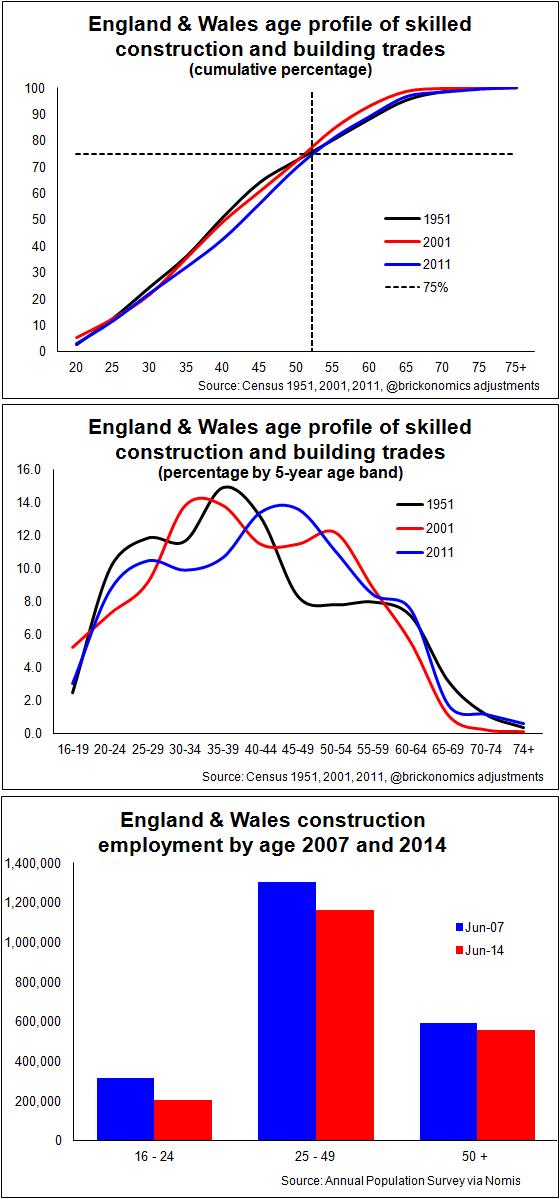

The results (top graphs) show a reasonably similar pattern for each of the census years. The cumulative total by age shows that in 2011 as in 2001 and 1951 about 75% of construction workforce is younger than 52.

The results (top graphs) show a reasonably similar pattern for each of the census years. The cumulative total by age shows that in 2011 as in 2001 and 1951 about 75% of construction workforce is younger than 52.

My estimate of the average age for construction workers is 41 years old in 1951, 38 years old in 2001 and 42 years old in 2011.

It’s probably risen a bit since then, but I’m not sure what data was used to provide an average age above 50.

The second graph is interesting and helps explain why you might sensibly think the average age of a construction worker has risen by 10 years over the past 10 years.

It shows that the peak age of construction workers has moved on by a decade. If we take the mode rather than the mean, the average has risen by about 10 years. 10 years ago when you visited a site the most common age would be in the 30s today it’s the 40s. So the reason you might think the typical construction workers is 10 years older is because it’s true.

But what’s happened since 2011 and what data might illustrate the shift in and out of the recession.

The third graph splits people by industry rather than occupation, but broadly it’s measuring a very similar group.

If we split the age bands into the core of 25 to 50 age group and those younger and older, the change does not look that worrying on this presentation. Comparing the near peak of June 2007 with June 2014 we see the changes are not that dramatic. The vast majority are still younger than 50.

Presented this way you might conclude that the problem has been overstated and it’s true that some of the figures pumped out do lean towards the apocalyptic.

But that would ignore the very severe threat on the horizon. This can be seen when we look again at the modal shift. Or, put another way, where the biggest group of workers sits on their construction working-life conveyor belts.

The overall age distribution for each of the 2001 and 2011 census years suggests that large numbers of workers leave the industry in their 50s. In 2001 the most common age for construction workers was between 30 and 40 years old, so there was plenty of working life in construction left in that group. In 2011 it was between 40 and 50 years old and that was four years ago.

If the pattern of the past continues plenty of these workers are now leaving the industry and we should expect the numbers retiring from construction to rise very rapidly unless ways are found to encourage them to stay on.

If ways are not found to retain older workers, they will have to be replaced in increasing numbers by new recruits if the industry is to avoid losing talent at an increasingly alarming rate.

Given that the industry lost about 400,000 workers during the recession, the task of rebuilding numbers will be tough enough without having to fill a gaping hole left by growing numbers of retirees.

This suggests that the industry should, if it is in anyway sensible, be looking not only to recruit more workers but also to find ways of usefully exploiting the talents of older employees.