Government must plan and act as if in the longer-term construction matters

In business certainty is a good thing. It may be less exciting for the crisis-management junkies we seem to be in Britain, but it helps us be more efficient.

There is however one certainty that is painful to experience. This is the certainty that an action or lack of action will lead to an unnecessarily destructive outcome.

Today the RICS launched its quarterly construction market survey. Its headline: “Private sector continues to provide forward momentum.”

It’s all pretty predictable stuff. Most firms see most sectors and most regions doing better than they were. Potted summary, things are on the up.

Sadly when I see such encouraging reports of the recovery of construction I am left pained and I have to say angry. This is not because I’m a miserable git who thrives on recessions, far from it. It’s great news that things have picked up. That we are building again. That we are investing in the necessary infrastructure to improve welfare and prosperity.

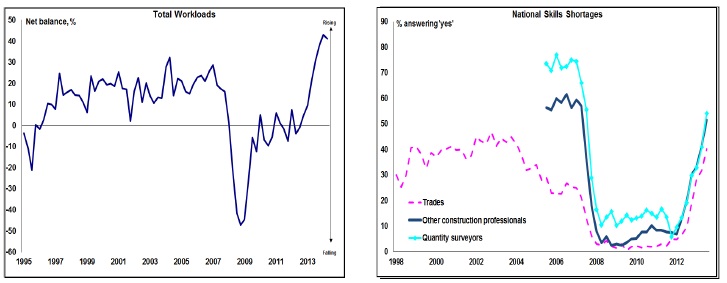

So why angry? Well I think there’s a clue in the juxtaposition of two graphs in the RICS survey release (see graphs below).

With the welcome upside comes the inevitable and totally predictable pain of seeing an industry struggling to cope with the demands put on it. The lack of available skilled people. An already ageing workforce on average four or five years older than before the recession. Frantic scurrying to foreign shores in search or skilled workers while young folk at home remain untrained and unemployed. A backlog of work that needs to be done but that may not be because of calls elsewhere. Inefficiency and rising costs. A supply chain debating on how much to invest in case it all goes pear-shaped again.

As much as anything can be certain in the unpredictable world of construction this was the inevitable outcome of the nation’s political and economic choices made during the recession. This is not smarmy clever-dick hindsight. It was predicted by many at the time.

But it was not inevitable. There were cards that could have been played to avoid it. Here’s just one blog from 2011, despairing at policy. There were plenty more before that.

The policy makers got it wrong. The Government could have invested in construction. Housing and the refurbishment of housing at the very least. We knew we needed it and we had the skills and supply chain in place.

The question we now have to consider is what should policy makers do from here on?

My gut feel is they will do little or any great value. Cut a bit of regulation here or there, invest a bit here or there where the private sector investment is a bit light, so it appears that we are all sharing in the recovery. Who knows?

What it will not do is investigate aggressively how we can boost the level of home-grown construction workers. There are more than a million 18 to 24 year-olds not in education that are either unemployed or not economically active. Surely construction can help here and in the process help itself?

We firstly need to stop blaming the young for their own plight, as if they were a breed apart. For that matter we need to stop thinking that the answer lies in making construction appear hip to the kids.

Much has been done, but we need more solid research to find the barriers and find the incentives that might work. Then we need to devise a plan and appropriate schemes to be tested. This should lead to a massive programme of job training and mentoring that is followed through with proper in-work experience.

This must be led from the top. From the Government.

What will happen is much handwringing, innumerable conferences, seminars, debates, meetings and policy papers from a host of different interested but ultimately impotent parties. This will lead to a few tepid showcase policies.

As they already are, construction firms will reinvigorate labour-agency contacts in Poland, Lithuanian, Latvia and anywhere else where they feel they can find workers of adequate skills. And this will be accompanied by much tut-tutting about how you can’t find a young British worker prepared to put in a full day on a Monday or a Friday because they would rather bunk off and go clubbing.

In an industry characterised increasingly by the self-employed, there will be little room and less incentive to bring on young construction workers, to provide the mentoring they need, to have the patience it may take to turn wayward teenagers into working adults.

Meanwhile, in parallel with this will be the major inquiry into why the Germans and not the English win World Cups.

Here’s my patronising suggestion of the day: plan and act as if the longer-term matters.