2012 will be a stinker for construction say forecasters

Construction industry forecasters are now expecting a drop in output next year of at least 5%.

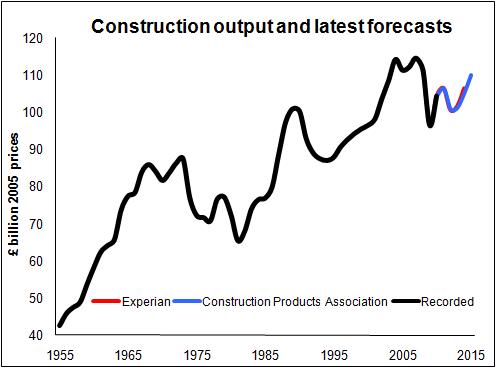

To put that fall in context, there have only been six worse years recorded since the data series began in 1955. And some might see the latest forecasts as potentially optimistic as they assume the Eurozone manages to muddle through its deepening crisis.

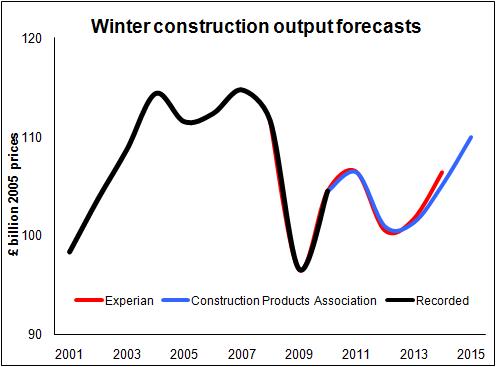

Interestingly the forecasts from the Construction Products Association and Experian are closer than they have been for some while, as the graph shows.

Both forecasts point to a sharp drop in output this year (5.2% and 5.6% respectively), the decline in output bottoming out in 2013 and a reasonable level of growth in 2014.

Both forecasts point to a sharp drop in output this year (5.2% and 5.6% respectively), the decline in output bottoming out in 2013 and a reasonable level of growth in 2014.

There are differences of emphasis. Experian tends to be more bullish than the Construction Products Association about the private sector, notably new housing, infrastructure and commercial building and more bearish about publicly-funded work.

It also tends to be more bullish about new work and less about repair and maintenance than the Construction Products Association.

But both sets of forecasts end up with a similar overall picture.

The first point to note is behind the forecasters’ decision to increase the projected drop in output in 2012 to more than 5% from around 3.5% is the better than expected performance of construction last year.

The public sector held up better than forecasters had expected and instead of seeing a decline in overall construction work last year, the data points to growth. The painful corollary of this “good news” is that the industry will fall in 2012 from a higher base.

On top of this the forecasters are generally less optimistic than they were a few months ago about the strength of the economy and, consequently, the recovery of private sector construction.

Put these two factors together and we get quite a big mark down in the forecast growth for 2012 and the prospect of 2012 being a very uncomfortable year indeed.

However, these are central forecasts – more a mode than mean. They point to what the forecasters think is the most likely outcome from a host of possible outcomes.

What is important to note when interpreting these forecasts is that the major risks are very weighted on the down side.

That is to say that there is a lot more chance of the reality for construction being a lot worse than forecast compared with the chance of things being very much better.

By far the biggest risk – in some eyes an inevitability – is a very untidy resolution to the Eurozone crisis. Should we see sovereign debt defaults then it would most likely kick the UK economy into a nasty nosedive.

The knock-on effect on construction would be extreme, on the assumption that the Government didn’t reverse its position on constraining public sector spending.

There are of course other potential big risks. We are seeing increasing amounts of speculation over the state of the Chinese economy, particularly in the light of its stubborn inflation.

There are of course other potential big risks. We are seeing increasing amounts of speculation over the state of the Chinese economy, particularly in the light of its stubborn inflation.

But against this we have seen slightly better figures from the US.

The point to note, however, is that with the prospects of recovery in construction resting solely on the private sector any market turmoil or uncertainty will slow growth.

To put the whole thing in a longer historical context, I have put together a graph for the data stretching back to 1955.