The problem with surprises on inflation

Could it be that we are about to witness the beginnings of widening concerns over rising inflation?

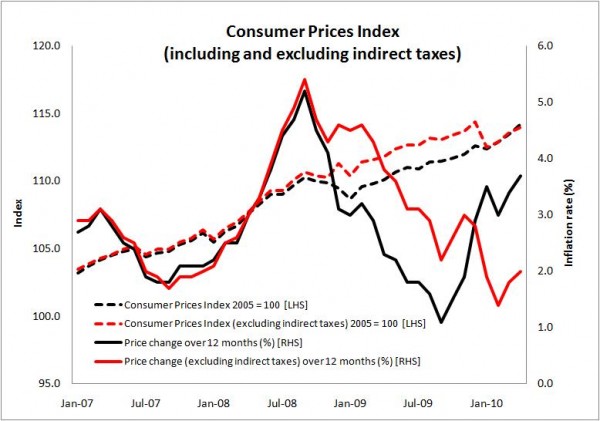

The Consumer Prices Index “surprise” jump to 3.7% yesterday will certainly increase rumblings in the markets and elsewhere.

Although for the time being I suspect attention will be more focused on June 22 and George Osborne’s first budget, which could after all produce some pretty hefty downward pressure on inflation, if the output from the rumour mill has any value.

Although for the time being I suspect attention will be more focused on June 22 and George Osborne’s first budget, which could after all produce some pretty hefty downward pressure on inflation, if the output from the rumour mill has any value.

However, if inflation does continue to “surprise” on the upside we may have to consider the implications of this on the credibility of the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee.

This is a point made by the BBC’s Stephanie Flanders in her Stephanomics blog post yesterday.

Any loss of credibility will not be good for either the UK economy as a whole or the construction industry in particular.

So how worried should we be?

In looking to illustrate the dangers of loss of credibility, the temptation is to use the extreme and suggest looking at the problems of Greece. But it is probably sufficient just to remind ourselves that credibility is central to stable financial management of an economy and currently the Bank of England is quite rightly held in high regard by the markets.

The price of a loss of credibility can be measured in various ways, but one result is the price at which we borrow. And with huge debts to pay this is not a time to be adding an extra burden on the interest payments.

To recap on the problem, the Bank of England forecasts for inflation, along with the predictions made by most economic forecasters, have tended to undershoot rather more frequently than simple chance would suggest.

Flanders neatly summarised the data on inflation “surprises” in an earlier blog of hers, so I refer you there.

For economic forecasters the consequence is mainly to damage their pride and reputation for foresight. For the Bank of England the consequences are more severe, particularly because the shading within the forecasts has been to underplay rather than overplay inflationary pressures.

There is, as Flanders points out, many voices that might suggest a conspiracy is afoot. And it would be worrying if this view took hold.

But it is true that inflation burns out debt and can be seen as a useful tool in equalising awkward lumps and bumps in the economy. Sadly its effect, when interest rates are low, is to spare the feckless borrower from pain at the expense of the prudent saver. Put another way a bit of inflation shrinks debt and that is handy for the UK right now.

If I’m honest, I have been extremely bemused by the Bank of England’s rather limp projections for inflation some while, as is clear from a range of earlier blogs, notably when I questioned whether inflation expectations were too low after the release of the November Inflation report.

But while its fair to accept that a wee bit more inflation than is normally tolerated might ease the pain of policy makers, I would not say it’s a conspiracy.

That said I have wondered whether the assumptions made about the amount of slack in the economy which underpin much of the analysis are less robust than the policy makers appear to suggest.

Furthermore, little seems to be made of the disinflationary effects that the UK should have, to a limited extent, enjoyed from the rebound of Sterling against the Euro of late, a jump of about 10% from its low point last year and more since the nadir in early 2009. In this light one might have thought the rise in inflation is a bit more worrying.

Still while I may have doubts, I fully concede that the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee has a strong case to remain unfazed by the latest figures, given the fiscal tightening that will come with the Budget.

But the markets may well reflect on the last two letters sent to successive Chancellors and wonder about the apparent slippage.

In February the Bank of England Governor Mervyn King wrote, that “inflation is more likely than not to fall back to the target in the second half of this year”.

In the latest letter King wrote: “The May projections also suggest that, absent further price level surprises, it is likely that inflation will fall back to target within a year.”

Admittedly these forecasts are fraught with the effects of cross-cutting variables and quite rightly carry heavy caveats. And many analysts broadly share the MPC’s view of inflation.

But markets are fickle and it is imperative that the Bank of England maintains its high level of credibility when it comes to being seen to control inflation.

The consensus appears to be that interest rates will remain low for some time yet. But there certainly remains a risk that if inflation remains uncomfortably stubborn before the effects of fiscal tightening really bear down.

The question then is whether the MPC would feel obliged to raise rates, if only to secure its reputation.