Why GDP growth is the most likely salvation for construction

There’s constant talk of this growth policy and that growth policy centred on construction. Big-looking numbers are bandied about. Then not a lot happens.

Perhaps that’s just politics in the modern media age where it is assumed that the memory of past policies is overwritten by the latest.

Cynicism aside, while the flim flam and bluster of politics is a barrier to getting useful things done, more worrying to me is a seeming lack of understanding of scale.

Put simply if we want to do anything of note with construction to turn the tide of the economy it must be huge, really huge. What is more it has to work. It seems foolhardy to base policies on speculation and hope.

Despite the bragging of lobbyists and the wishful thinking of industry leaders, the impact of most Government interventions pale against the larger economic forces.

Yes Government interventions can be important, but ultimately what has driven the fortunes of construction over the past half a century has been GDP growth. And the strong link with GDP growth and construction growth is not limited to the UK.

To illustrate this and in the name of efficiency I shall recycle some charts from a recent presentation to CIC Economic and Policy Forum. My central point then was that the Budget measures were pretty piffling given the scale of the challenge and the economic environment and expectations.

To illustrate this and in the name of efficiency I shall recycle some charts from a recent presentation to CIC Economic and Policy Forum. My central point then was that the Budget measures were pretty piffling given the scale of the challenge and the economic environment and expectations.

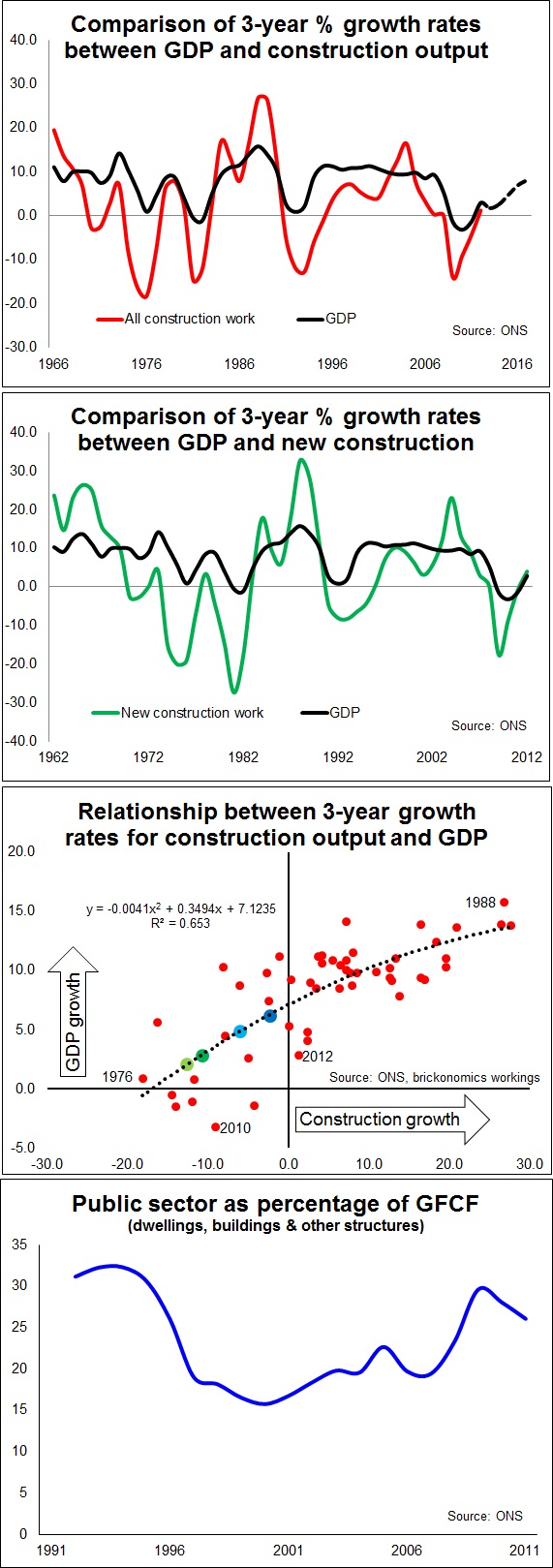

The first graph compares GDP growth and construction output growth over three years. This seems a reasonable timescale over which to judge the two and it also dampens the noise. I have added the GDP forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in a dotted line.

It is clear that construction is very procyclical. Certainly we see that when there has been little GDP growth over three years construction has dived into recession.

The second graph shows the comparison with construction new work. The relationship is far more severe.

This third graph plots the three year growth rates for GDP and construction output for the past 50 years. What we see is a pretty strong correlation. Interestingly on the five occasions when the three-year growth rate for GDP has been negative we have seen no construction growth over the same three years.

The coloured dots on the trend line are derived from the OBR forecast for GDP growth, suggesting where three-year GDP growth will be as it rises from 2013 to 2016.

Crudely put you might expect on average to need about 7% growth in GDP over three years to see construction growth over the same timeframe. Worryingly the consensus of forecasts published by the Treasury suggest GDP growth over the coming three years of about 5%.

Now there are a lot of base effects (where are we now relatively?) to take into account. But the figures don’t provide much room for optimism, particularly as private sector investment in construction (the bulk) will be in large part determined by the path of the economy.

The final graph shows the public sector proportion of the nation’s gross fixed capital formation for dwellings, other buildings and structures. It is not a perfect measure, but it does suggests that the public sector accounts for somewhere between 20% and 30% of the fruits of construction and the proportion is falling.

So for the public sector to have a meaningful direct impact on construction it would seem the scale must be large.

Alternatively the public sector could spend a bit less if it could find effective ways to lever new private sector investment. But for my money such a policy really should be based on what we know will work rather than on some speculative albeit well-meaning hope of what might work.

Recent public sector policies have focused on prompting private sector investors and businesses into building and on coaxing households to buy more new houses. In a sense seeking to prop up the collapsed market.

These were always suspect. In housing there is a market failure that predates the financial crisis. In the commercial sector there is huge structural change. In infrastructure there is the ever present level of high risk, and the economic uncertainty doesn’t make that attractive against investment elsewhere.

Furthermore dragging on all these markets has been the dead weight of negative, slow and no growth in the economy overall.

So it is little wonder that the prompts have not really been that effective, although we don’t know the counterfactual. Maybe construction activity would have been much worse without these interventions.

The other side of policy has been to point to supply-side inefficiencies, such as planning. Frankly improving the efficiency of the processes is a long-term fix and it is extremely unlikely that such policies will be effective enough to perk up construction in the short term. Rather such policies introduce the possible danger of confusing investors with uncertainty and changes to the ground rules.

All that however is a bit of a sideshow debate. The real questions are firstly, how important is it to get construction motoring? And, secondly, what actually should be done now to drive construction growth?

The first to me is simple. Build now when resources are cheap and reap the benefits over the coming decades. Trust me, it’s a good move and a wasted opportunity if you don’t.

The second question is more interesting and stewed in the politics of the day. In my view the Government should spend large and spend directly on construction. It can borrow extremely cheaply and for all its borrowing there will be an asset of most likely greater value stack against it.

We need infrastructure. We need housing. We need to transform large parts of our cities. We will need all this even more in the future when it will cost us more.

In my view we need these urgently and hoping to tease a coy private sector into action when it is quite rightly nervous seems a rather limp approach to a tough problem.

Ultimately the best hope for construction growth will be in restoring growth to the economy. But wouldn’t it be sweet if construction could be a catalyst for that.