Restructuring stamp duty should provide a boost to housing, interesting timing don’t you think?

So the Chancellor’s big idea was a reform of the stamp duty land tax.

Excellent.

Certainly few people with an appreciation of either taxation systems or the housing market think SDLT is a good tax.

The Mirrlees Review: A proposal for systematic tax reform, a highly-regarded document in tax circles, had this to say for it: “There is no sound case for maintaining stamp duty and we believe that it should be abolished.” It recommended it be replaced by a land tax.

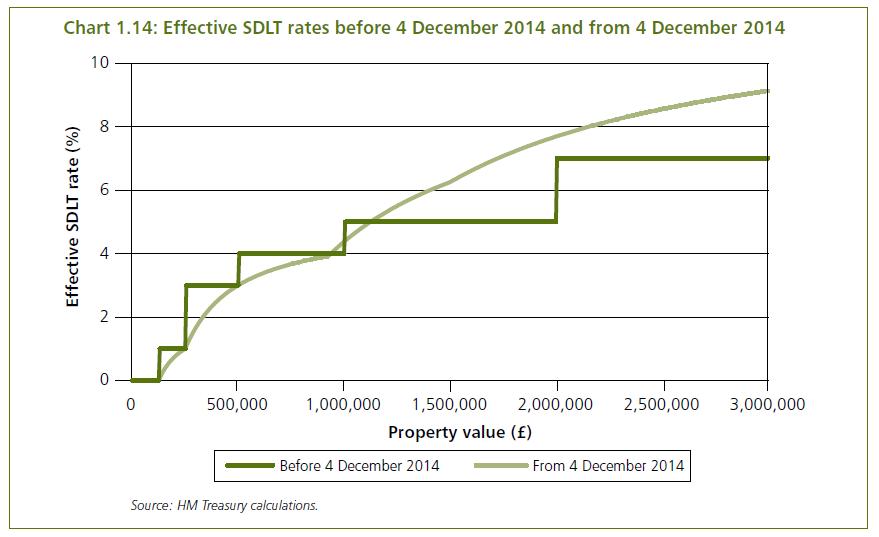

However, earlier in its discussion of SDLT the review did say: “The ‘slab’ rate structure … is especially perverse, meaning that transactions of very similar value are discouraged to completely different degrees and creating enormous incentives to keep prices just below the relevant thresholds.”

It is that “slab” bit that the Chancellor has seen to, leading to much joy, especially, I’m sure, among estate agents.

The various likely effects of George Osborne’s restructuring of SDLT can be read, to some extent. The overall effect is much harder to compute fully.

One potential effect is flagged up in the Mirrlees review. It suggests that “removing it would create windfall gains for existing owners, as it will largely have been capitalized into property values”. So those who are looking to sell a home currently priced in a range where the tax take would fall will probably raise their asking price and make gains on the sale. This might cause a spurt in prices at particular price points.

Meanwhile, buyers are also likely to share in the gain. They, after all, have to find the cash to pay for the duty in a lump sum. This can be prohibitive, as they also seek to build up a deposit and look for cash to cover the other fees needed to buy a home. So the change in the SDLT structure should create a boost to sales, again differently at different price points, but especially among first-time buyers with limited equity. The Chancellor’s change should increase demand and transactions, at least in the short term.

This surge in transactions should also be supported as sellers seeking a price just above a threshold in the old SDLT rate will now find buyers more willing to accept that price rather than seek to push it below the threshold. This should mean more acceptable offers and more deals done.

So, broadly speaking, we should expect to see dotted at points along the price band (up to £1 million) more transactions and slight spikes in house price inflation.

Looking at the new-build sector we should expect a large cheer from house builders, as they capitalise some of the SDLT reductions into selling prices and see a jump in interest from buyers (especially first-time buyers).

We might also expect to see subtle changes to the new housing mix, as builders pitch homes into the market more freely around what were awkward price points around the SDLT thresholds.

We might also expect to see subtle changes to the new housing mix, as builders pitch homes into the market more freely around what were awkward price points around the SDLT thresholds.

Importantly where the SDLT take is set to fall is where most action takes place in the market. This should help to increase the overall level of transactions.

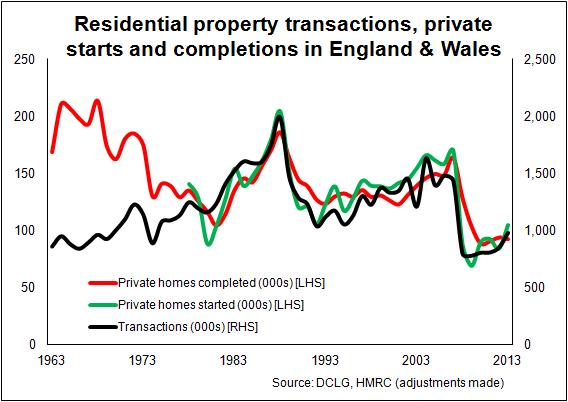

And, just as more points mean more prizes, more transactions should mean more new homes built. As we can see from the top graph, this has been the case for the past 40 years or so.

So a lot of relatively positive things should happen in the short term in the price ranges below about £1 million, at which point the tax increases for all sales (see lower graph taken from the HM Treasury Autumn Statement 2014). Naturally the effects of the restructuring will vary regionally.

With all tax changes there are short and long-term effects and they can be very different. Ultimately, the change in SDLT will increasingly seep into house prices and land prices where it is reduced and be sucked out of house prices and land prices where the tax take is increased.

With all tax changes there are short and long-term effects and they can be very different. Ultimately, the change in SDLT will increasingly seep into house prices and land prices where it is reduced and be sucked out of house prices and land prices where the tax take is increased.

But a word of caution, SDLT is still a rubbish tax, although slightly better without its slab structure. A land tax would be a more reasonable, fairer and economically efficient option and, in theory at least, would do more to stabilise house prices.

The net result of this move by the Chancellor may be to make it easier in the short term to step on the housing ladder, but lead to higher house prices in the long run. This would increase the gaps between the rungs of the ladder, making it harder to climb.

There is, of course, one other issue to chew on. Why has this change been made now as a last throw before the election?

This tax has been a potential drag on housing transactions and house building for a long while. Certainly it has been a greater drag than normal through the nearly five years of George Osborne’s tenure as Chancellor, when the problems faced by first-time buyers trying to raise enough cash to buy into housing have been severe enough for him to introduce incentives such as Help to Buy to reduce the burden.

Interestingly the restructuring of SDLT should, as we discussed above, give the market and house building a short-term boost, neatly ahead of next May’s election.

Surely, as a servant of the public, the Chancellor cares more for the long-term housing needs of the nation than his short-term appeal ahead of the polls?

Or is there something I’m not getting about politics?