Has the Government found a cure for the disease afflicting the housing market?

The short answer to the question in the headline is no. The slightly longer answer requires a question: It depends what you mean by the housing market?

But, as that sounds like obfuscation, the most honest answer I can come up with is that while the housing market may appear to be in remission the disease is spreading.

I say this because we’ve had such a welter of “good news” on the housing front recently that you’d could be forgiven for thinking “job done”. Today brings more.

The survey by the surveyors’ body RICS suggests that the pace of house price inflation is gathering pace and spreading across the country and the queues of potential buyers are getting longer.

The ONS house price survey shows house price inflation rising.

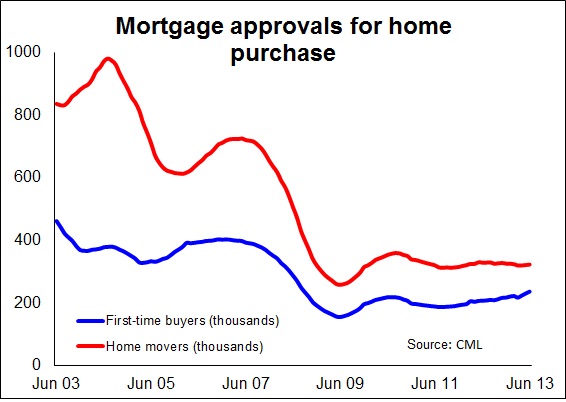

The latest first-time-buyer data from the Council for Mortgages Lenders suggest lending to this cohort hit its highest level since 2007.

To the man and woman in the street, or more probably in their owner-occupied home, this all looks promising. And don’t get me wrong benefits will flow from this greater activity.

But all this focus on the “good news” really rather misses the point. And, if anything, much of the good news simply reflects the fact that the market, in terms of turnover at least, had few places to go but up, given how completely screwed it had become.

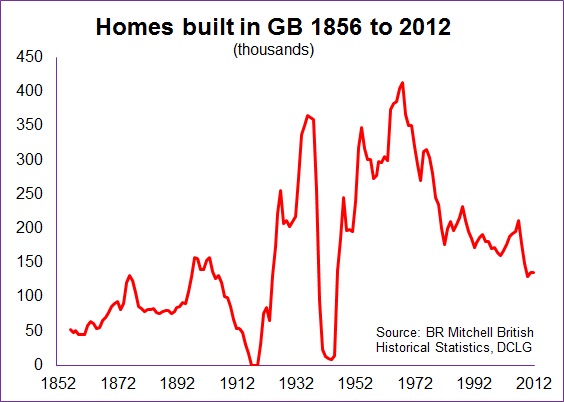

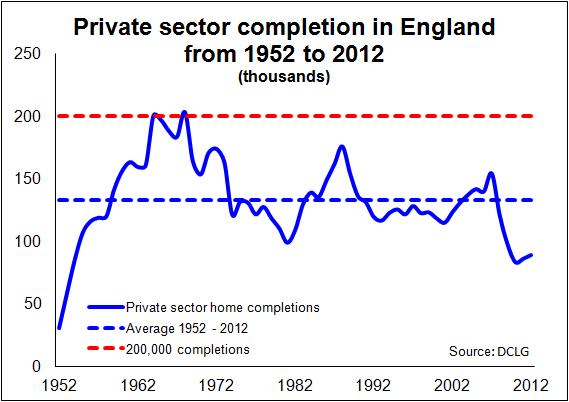

The historical graph I cobbled together using data from BR Mitchell’s British Historic Statistics and DCLG rather sets the scene in terms of how many homes we are building today compared with the past.

The historical graph I cobbled together using data from BR Mitchell’s British Historic Statistics and DCLG rather sets the scene in terms of how many homes we are building today compared with the past.

Some context: The population of the UK rose by about 4 million between the census of 2001 and the census of 2011. We are currently enjoying a baby boom. The UK is one of the faster growing developed nations, as well as being and one of the richest.

Yet house building is, to use the vernacular, on its arse. We built few more than 140,000 homes in the UK last year. That’s about half the number built in the mid 1970s when the population actually fell in some years.

We have overcrowding. We have high prices. Rents are rising rapidly. We have homelessness. We have too few homes to allow for choice and easy movement from one home to another. And, yes, aspirant young people can’t get themselves on the path to homeownership.

While for many of us in the UK housing is comfort and security. For increasing numbers it is inadequate by any standards for a rich nation, it is a worry, a frustration and unhealthy.

Ironically we spend a significantly higher proportion of our income on housing nowadays compared with years past.

This to me does not appear to be evidence of a sound housing market. It is a very sick housing market.

I’ve boiled down the problems to five broad areas (though I’m sure you could divide things differently and suggest other categories):

- The stock is too low, particularly given the way it is distributed

- The rate of increase in the stock is too low to accommodate the demographic pressures and address the underlying lack of stock

- Housing is too expensive for a large section of society, either to rent or buy

- Young people on average struggle harder to finance home ownership than their parents

- Transactions are very low. This has two particular impacts, firstly homeowners find it harder to move, secondly house builders build fewer homes for sale

These problems are all interlinked as you would expect in a complex system.

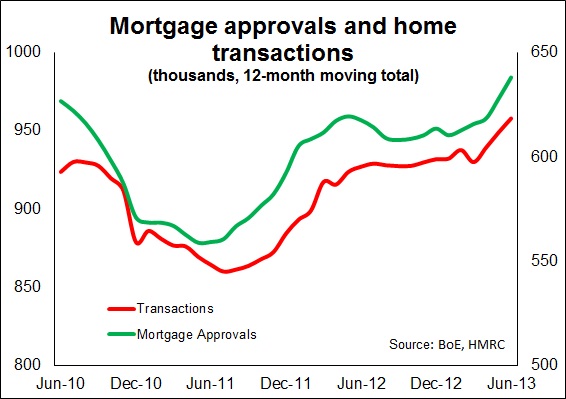

What we see following the introduction of the Funding for Lending Scheme (providing more money for mortgages) and the first phase of Help to Buy (making it easier to access that money) is an increase in demand. Many who had felt locked out of buying into or trading within the housing market now can get mortgages, with the prospect of this scope widening with phase two of the Help to Buy scheme.

What we see following the introduction of the Funding for Lending Scheme (providing more money for mortgages) and the first phase of Help to Buy (making it easier to access that money) is an increase in demand. Many who had felt locked out of buying into or trading within the housing market now can get mortgages, with the prospect of this scope widening with phase two of the Help to Buy scheme.

This increase in demand is evident in the Bank of England figures and the CML figures, which show a steady increase in the number of home loans, in the case of the latter to first-time buyers. There has also, it might be added, been a significant rise in Buy-to-Let mortgages.

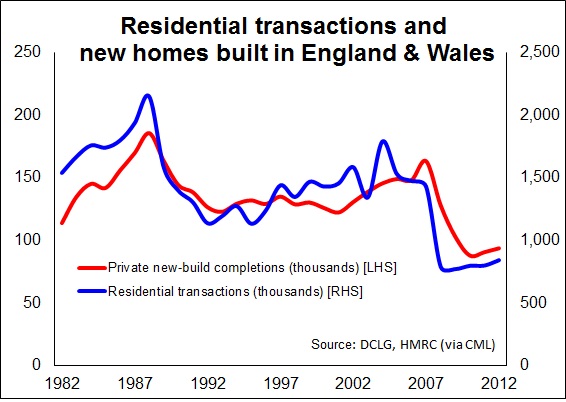

This has meant more transactions, which should lead to more building of new homes. There has been an intimate link between transactions and private sector house building since the 1970s and there is little reason to suspect that this has broken. Broadly of each 10 homes sold one is a new home.

But while transactions may rise (potentially quite markedly), the relationship suggests they would need to double to restore us to the levels seen pre-crash. This is a big ask. The chances are far more remote of lifting the private sector to a level of home building that policy makers back in 2007 suggested was needed to defuse the housing crisis.

So, summarising, it seems fair to say that the impact of FLS and H2B (as they seem to be written these days) has increased demand and this appears to have raised transactions and in doing so it should raise supply, at least a bit.

This will do something to improve problems 4 and 5, although the problems are likely to persist. But as for problem 1, this will worsen. Problem 2 may ease a shade, but it will be very far from cured.

What of the thornier issue of problem 3? There is a fear that coming on the back of the FLS, Help to Buy will fuel house price inflation. If this happens, and there’s plenty to suggest it could, the problems related to the cost of housing will worsen.

Also, if house prices rise fast it will lead to first-time buyers, having been shown a door opening, being locked out again. In turn higher house prices will raise land prices and the spiral of costs that feed into house building.

I have concerns over the Help to Buy scheme. I’m not alone and it worries me somewhat when the greater majority of economists, a business organisations such as the Institute of Directors and the IMF all point to Help to Buy as a bad policy. I was particularly struck by the easy way that the Economist magazine dismissed it as “a daft new government-subsidy scheme”.

The scheme will benefit house builders, at least in the short term. It will please a host of homeowners and potential home owners. It will most likely generate a consumer-led stimulus for the economy.

As a short-term measure to kickstart the economy, you might argue these are not bad things to do.

What bothers me is that, sadly, the motivation seems to be more medium term. Aimed at May 2015 when the polls open on General Election day.

What’s more the policy is high risk and there are many who feel it will simply deepen the existing failings of the housing market.

The failure to act more decisively and faster to stem the fall in house building at the outset in 2008 means that the stock shortfall is greater than it need be. Had we maintained building at the already inadequate rate at which we built in England in 2007 we would now have about 300,000 more homes than we do. We would have nearer 500,000 if we had built to meet the aspirations of the policy makers in 2007.

Given the shortfall we can and should expect the private sector house builders to do some of the heavy lifting to get the number of homes built up to a more acceptable level. But they cannot be expected to do it all, however much they are coaxed by Government.

While the final graph gives a broad hint why, I suspect the reality is worse than it appears on the chart. I suspect it is tougher, for a number of reasons, today than in the past for the private sector to ramp up production. If we were to set a level of 200,000 for the private sector to acheive we can see that this has seldom been hit over the past 60 years, only twice in the raging 1960s.

The average over the past 60 years is 133,000 a year. Even reaching that might seem a reasonable acheivement given the hole we are in. What we must also remember is that mortgage rates will rise above the current very low levels. When? Who knows? But this will cool the market.

I have not thought since the outset of the house-building collapse in 2008 that there is any real alternative than for the Government, if it truly wants more homes to be built in the UK, to instigate building a huge slice of those homes needed itself, in a more direct fashion.

I have not thought since the outset of the house-building collapse in 2008 that there is any real alternative than for the Government, if it truly wants more homes to be built in the UK, to instigate building a huge slice of those homes needed itself, in a more direct fashion.

If we need more homes and it would be good for society and the economy, then the simple answer is to build them. In former days this was recognised, accepted and acted upon even in times when the nation’s debt was proportionately higher.

I have no illusions that the solution to the intensifying housing crisis in Britain is simply about building more homes. But building more homes today would go a long way to easing many of the five problems outline above. It would benefit most people in the nation in the long term, not just the immediate problems facing some people in the short term.

One thing caught my eye today and amused me. The Office for National Statistics released two sets of inflation figures, the consumer prices figures and the housing market figures. One went down and was welcomed. One went up and was applauded. What an weird world we live in.