Why jobs in construction are increasingly valuable for the UK and should be nurtured

A few weeks ago I received a request from Dan Earley a quantity surveying student asking for a comment on training and development within the construction industry.

I was delighted to help, in part because it prompted me to write some words that had been sitting in my head for some while.

I had meant to post the comment on this blog, but it slipped from my memory and down the pile in the guilt tray.

Yesterday’s fantastic ONS release on 170 years of industrial change reminded me and prompted me to post it.

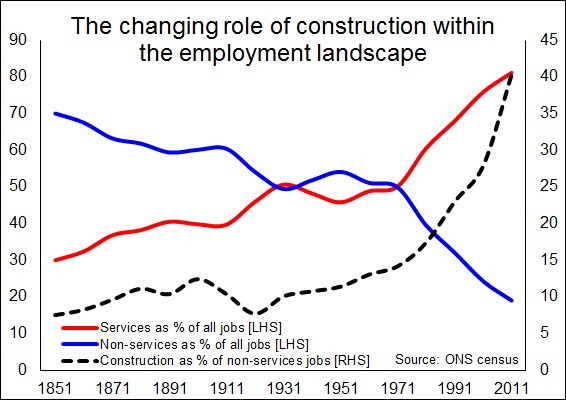

Here’s a chart produced from the data published by ONS. I have made some estimates from the census for the missing 1971 data.

The central point is that construction is increasingly important as it offers an ever increasing proportion of the manual jobs on offer within the economy as the black dotted line clearly illustrates. More than 40% of the jobs in the predominantly manual sectors are now in construction.

The central point is that construction is increasingly important as it offers an ever increasing proportion of the manual jobs on offer within the economy as the black dotted line clearly illustrates. More than 40% of the jobs in the predominantly manual sectors are now in construction.

And here below is the note I sent to Dan. The figures used in the script may vary slightly from those provided by the census as they were taken from the employment data series, but the message remains the same.

“A quarter of a century ago industries that employed mainly manual jobs, such as agriculture, fishing, mining, construction and manufacturing, accounted for more than a third of all employment.

Roughly 10 million of the 27 million jobs in the UK were to be found in these sectors of the economy.

The proportion of manual jobs in the economy had already been in decline for some while, but from the late 1970s the acceleration in technology and the relative growth of the service sector changed the landscape.

The past 25 years have seen the number of manual jobs decline rapidly both in number and as a share of the available employment. Today they number fewer than 5.5 million and represent just 17% of the workforce. Furthermore the level of manual skills jobs will have fallen within those industries as the proportion of administrative, technical and managerial jobs has risen.

One can get sentimental over the loss of these jobs. That serves little purpose. But there is one certainty, their loss is denying many young folk, particularly young males, who didn’t excel at school an opportunity to get back on track and develop both trade and life skills.

We see the social consequences.

Importantly while the number of manual jobs available overall has halved, the level of the construction workforce is as large today as it was in 1978. What’s more a fair slice of manufacturing jobs are construction related.

Construction will for the foreseeable future at least continue to provide manual jobs in large numbers. It therefore is playing an ever important role in providing those much-needed opportunities to school leavers not necessarily comfortable or with the right outlook to easily adapt to working in offices or shops or working in social services.

If we extend this idea further, construction offers a solution to kids from deprived backgrounds with bags of energy that today is undirected and sadly too often misdirected.

It is a national shame that when faced with a construction skills shortage a decade ago the construction industry felt obliged to seek hundreds of thousands of workers from abroad. Yes it is good to have open borders for employment, but we could and should as a nation have seized the opportunity to invest heavily in turning kids who have lost their way into young adults who have found construction as a solution to their futures.

As a nation we should have invested and worked to lift both the skills and the attitudes of more young British people to a level where they could compete with the highly skilled, highly motivated folk who brought their talents here.

We should have got the message out to more to young kids that they were more likely to become a millionaire by working in construction than by seeking a career in professional football or music. We should have shown them how they would have more opportunity to be their own boss in construction than in any other industry.

And we should have made it clear that even if they failed to reach these high aspirations, they would still have a sound trade on which to build for the future.

But that is just part of what we could have done and still should do.

If you talked to almost any subcontractor in the boom times they would have told you that the reason they employed a Pole or a Hungarian instead of a young local was attitude. Those from abroad who chose to ply their trade in London, Bristol or Newcastle worked hard, they turned up on time, they did a fair days work, often more, and they had good skills.

We can dismiss the problem of a poor attitude among elements of British youth as an unchangeable feature of modern life. But that is to repeat what has been said generation after generation. It is defeatism and it is to shed our responsibility both as adults and as a nation.

We focus a lot on skills in the UK. We need to focus much more on attitudes. For some kids we need to offer mentoring, provide them with role models. For some we need to find ways to shield them from the pull of social settings that drag them away from self-improvement.

This may mean disrupting misplaced political correctness. This may mean forcing the indifferent and the uncaring to action. But to dismiss a slice of our population as we have been is to recycle and expand a real problem that we have seen growing over the past few decades.

As I see it construction can be a vital part of a solution. We just need the right attitude and to find ways of instilling the right attitude in our youth.

That requires much-needed investment. But that investment promises very high social and economic returns.”