Be prepared for a very different construction industry when we rise from depression

This is no ordinary recession. This is a serious depression, the end of which still looks to be at least a couple of years away and possibly a lot further.

If that proves the case it would have lasted longer than the Great Depression of the 1930s, although the recession would not have been as quite as deep.

The well respected economist and Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf recently wrote: “The UK is in the midst of what is set to be the longest – and among the most costly – of its depressions in over a century. The characteristic of this depression, compared with its predecessors, is the frightening weakness of the recovery phase.”

The question for those in construction is how this economic horror show translates into patterns that will determine the size and shape of the industry in the coming years and, as the industry rises from recession, where will the opportunities lie.

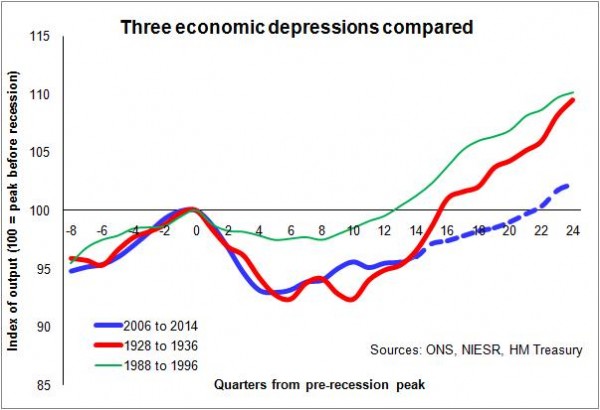

Before looking ahead, to get an idea of the scale of the current depression and where we are, I have put together graph 1 to compare three depressions, the “Great Depression”, the depression associated with the 1990s recession and the current depression. It shows just how bad things are economically.

Before looking ahead, to get an idea of the scale of the current depression and where we are, I have put together graph 1 to compare three depressions, the “Great Depression”, the depression associated with the 1990s recession and the current depression. It shows just how bad things are economically.

For reference, there are various definitions of a depression. The one I have used here is the period during which GDP remains below the previous peak. The numbers showing quarterly GDP during the 1930s Great Depression come from a discussion paper produced for the National Institute of Economic and Social Research by Solomos Solomou, James Mitchell and Martin Weale, now a member of the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee.

And the projection for economic recovery from this recession is taken from the average of the Treasury comparisons of independent forecasts to 2015 compiled in August. Things probably look a little bleaker now.

Before we despair too much, it’s worth noting that economic depression doesn’t necessarily spell disaster for construction.

In the 1930s construction ended up a beneficiary of the crisis. As official interest rates were slashed to 2%, cheap money fuelled a private sector housing boom the likes of which we have not seen since. Meanwhile in the US a massive Government investment in construction was a major driver of the recovery.

But this time around in the UK, with huge cuts to public spending and a stagnant housing market that is not responding to exceptionally cheap money, it is hard to imagine how construction might fare.

Unless there is a major policy shift, we know that in this recession the construction industry is totally reliant on the private sector for recovery. Furthermore the private sector will also have to fill the gap left by £10 billion or so of annual public spending that is forecast to be axed from construction over the three years 2011 to 2013.

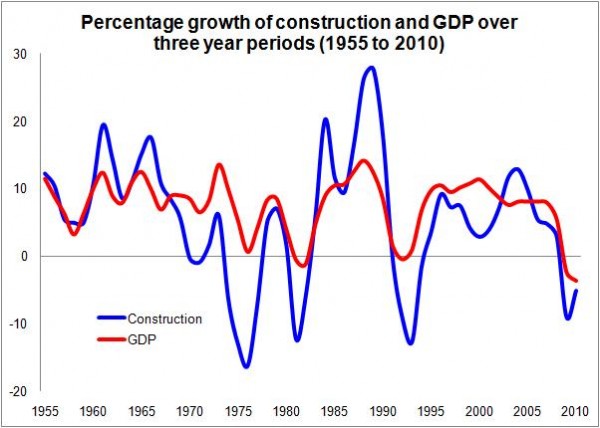

More concerning is that recent history suggests that construction output and private sector construction in particularly tends to broadly track swings in GDP, but in an exaggerated manner. Negative or low GDP growth tends to mean recession for construction, as we can see from graph 2, which shows the growth of construction output and GDP on a rolling three year basis to smooth some of the volatility.

More concerning is that recent history suggests that construction output and private sector construction in particularly tends to broadly track swings in GDP, but in an exaggerated manner. Negative or low GDP growth tends to mean recession for construction, as we can see from graph 2, which shows the growth of construction output and GDP on a rolling three year basis to smooth some of the volatility.

But GDP is not the only determinant of construction.

From a construction point of view what’s important is that, as economic and social activity change, the whole built environment needs to be adapted to match the newly emerging patterns of production, service delivery and lifestyles. This creates demand for construction.

The flip side is that economic and social transformation also destroys demand, as types of building or structure become redundant.

One could get hung up or indeed bogged down in definitions and theory over cause and effect in the relationship between business cycles and what economists (particularly those who follow the work of Joseph Schumpeter) might want to call “creative destruction” – the process by which the old order is destroyed to make way for the new order.

But considered in folksy terms, economic crises often provide an environment that spawns major changes to the fundaments of an economy, or indeed society. Economic turmoil weakens the hold of outmoded but entrenched institutions and business structures. They are rattled and collapse, paving the ways of doing business.

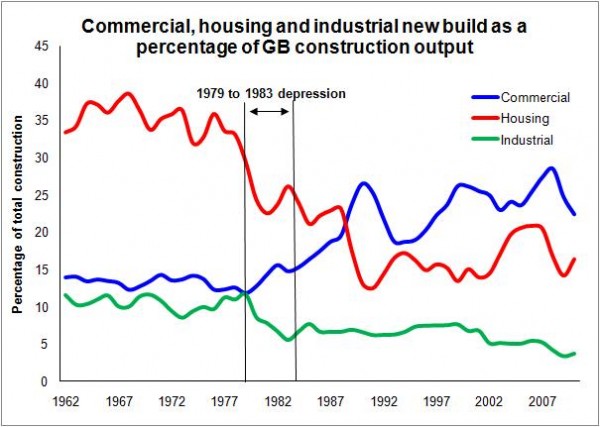

So in graph 3 we can see the profound shift in the construction mix during the late 1970s and early 1980s as the balance of UK economic activity shifted from production to services.

So in graph 3 we can see the profound shift in the construction mix during the late 1970s and early 1980s as the balance of UK economic activity shifted from production to services.

If we look at the period between the lines that represent the 1980s depression, we can see a quite marked shift in the proportions of commercial construction and industrial-related construction. And this divergence continued as the economy grew.

The graph also shows how house building receded sharply in this period. This in large part was a result of needs and demand falling following relatively high levels of post-War residential development and as population growth slowed markedly after the introduction of the pill.

With the benefit of hindsight we can see how this period might be seen to represent a paradigm shift for construction. There was a step change up in commercial investment in construction and a step change down in industrial related work. And, as mentioned, a major shift down in house building numbers.

If we look back to the 1990s recession it did create quite marked change, but not particularly in the mix of construction work. The change in the 1990s was centred on new management thinking and cultural change to organisations.

There were shifts in the mix of work, but they were more subtle. Spending on health and education-related work grew rapidly as a proportion of spending, as did entertainment. But for the most part the shift was not dramatic.

Interestingly there was perhaps a more marked shift in workload mix within sectors. If we look at infrastructure, road building came under huge pressure as the recession loomed. After the recession it never really bounced back. Rail spending, meanwhile, expanded. The ratio of road work to rail work in the early 1980s was about ten to one. The spending on road and rail today is not that far off equal.

This shift probably owes more to the changing social values that emerged in the 1990s towards environmental sustainability than it does to economics. But again it might be argued that recession was a catalyst.

So what kind of recession is this? Is it a game changer that will result in the mix of construction work being very different when the economy finally rises from the depression?

In truth no one really knows what lies ahead, but there are clues.

We can certainly say that the drop in public sector spending will alter the mix markedly.

But, leaving that to one side, there are two drivers, at least, that I personally see that might come right to the fore in this depression to promote a fundamental shift in construction industry output.

The first is the impact of information technology. While computing technology has allowed increasingly for remote working, the spread and cultural acceptance of broadband, mobile devices and cloud computing allows for far greater flexibility over when and where people work today than was probably true even five years ago.

It is now much easier than it was to move the work to the workers rather than having to move the workers to their work.

Recent research by the Future Foundation suggests there is a growing acceptance that the coming decade will see a leap forward in how some businesses reorganise themselves to tap the full benefits of these collaborative business tools and the opportunities for creating virtual organisations.

The second driver is a downward pressure on real earnings growth. I strongly suspect that for most of us improvements in real earnings will be far more hard won in the years ahead than they were throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, when globalisation created disinflationary forces in the UK economy with the flood of cheap goods.

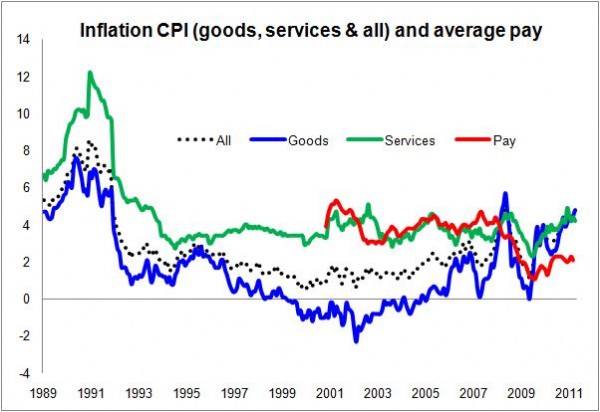

Graph 4 shows how pay in the previous decade tended to track with services inflation, which is no surprise as this is mostly home grown. Meanwhile cheap goods, largely imported, dragged down inflation overall.

Graph 4 shows how pay in the previous decade tended to track with services inflation, which is no surprise as this is mostly home grown. Meanwhile cheap goods, largely imported, dragged down inflation overall.

Assuming there is something in the notion of a broad connection between services inflation and pay over that period, then above-inflation pay rises were pretty much guaranteed for the majority of the UK workforce over the past two decades, if the Bank of England was to hit its overall CPI target of 2%.

This “golden period” has come to an end. Certainly, that is what the recent data suggest. More concerning, however, is whether there is a prospect for a reversal where we start to import goods inflation as pay rises accelerate and productivity gains slow within the exporting emerging economies. This would press down harder on wage rates.

Either way the fundamentals suggest that the prospects for wage rises in relation to inflation look pretty bleak in comparison with the buoyant pre-recessionary times.

For employers in the services sector (the majority in the UK economy) this presents a headache. If goods inflation rises and we have little control over it as it is largely imported, the pressure will be on containing services inflation and so pay in the services sector will be heavily constrained.

Employers keen not to lose staff though pitiful pay rises will have to work harder to find smarter processes to raise productivity or drive down overheads costs. This tough commercial pressure will force firms, especially in the service sector, to squeeze spending on offices and associated servicing.

They will inevitably look eagerly at the opportunities technology present for more at-home or out-of-office working in conjunction with hotdesking. We are already seeing this happen.

It is easy to imagine the rise of targeted brands of pay-as-you-use offices dotted across the country, providing all the facilities corporate offices can offer (and more) for independent professional to corporate employees, who once would have occupied dedicated regional offices. This image fits neatly too with the growing enthusiasm for coworking.

Shifting fixed office costs to variable pay-as-you-use terms would not just cut overhead, but would also give firms and employees more flexibility opening further productivity gains through the time saving of moving work to the worker rather than the worker to their work.

Even a fairly modest fall in office occupancy might create significant downward pressure on aggregate demand. Naturally the growth in the working population is critical. But much of the commercial construction work of the past three decades was based on expanding the office stock (an increase of a quarter in the past decade alone).

Meanwhile, the standout statistic for shops and shopping is that Internet sales now account for 10% of total retail sales, having doubled over the past three years. Even if the growth rate eases sharply, Internet sales look set to push in-store retailing into decline over the next few years.

It’s hard to imagine how the retail estate as we know it can remain unaffected faced with lower-overhead Internet sales. The pattern will be patchy across products and services, but we might expect to see a radically different, probably smaller, retail estate in 10 years time. Indeed, will some “shops” be little more than permanent exhibitions for goods bought on line?

Of course population and economic growth (eventually) will buoy the offices and retail sectors. And it seems highly improbable that swathes of shops and offices will be swept away as we saw factories levelled throughout the 1980s.

But if the pattern of demand and usage of shops and offices change radically – a given for the massive public sector estate – the construction industry’s role will shift markedly toward transforming rather than adding to the stock.

Where there will be pressure to add stock is within housing, an irony given so few homes are being built. Beyond this there will be opportunity for firms in the sector to respond to the increasing and changing demands we put on the home as a workplace and place of entertainment.

While it’s relatively easy to imagine the needs and desires for buildings and structure in the future, in the end effective demand in the form of hard cash will determine the precise mix of construction work.

But there’s much to suggest that rather than renewing and extending the nation’s estate the construction industry will be pressed increasingly to reshape it to support a much changed economic and business environment.

Despite the pain this may cause, for some this will be a time of great opportunity if they can anticipate the needs of tomorrow and meet them with creative solutions in design, management and financing. For those who can’t or don’t want to destruction beckons.

2 thoughts on “Be prepared for a very different construction industry when we rise from depression”

A very interesting read.

As the last boom was beginning to cool and we entered recession my thoughts switched to which innovative solutions will drive us forward over the next 10-15 years.

Sadly at the moment nothing is obvious, which in turn leaves a liitle uncertainty where the next development projects will come from in the construction industry.

My only hope is that this recession will allow the west to be more realistic in manufacturing costs and leaner to compete with the growing far east markets and we all begin to purchase a little nearer to home.

found the recession profiles very interesting. trying to do some research on the great depression, any chance there is a site which provides quarterly data for the depression of the 1930s

Comments are closed.