Why a 1930s style private-sector house-building boom seems highly unlikely

As the parallels with the 1930s depression become increasingly unavoidable, I sense a new romantic surge of interest in the notion of a private-sector-led house-building boom driving economic recovery.

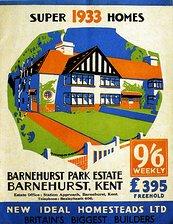

For those not familiar with the 1930s private house building market, completions in England in 1934 hit almost 290,000. That is near on three time current levels. Never before nor since has there been such numbers of private homes built in England.

The public sector was not workshy over that period either. Over the 1930s local authorities in England built more than 60,000 homes a year.

It was a golden age of house building, fuelled by cheap money and huge demand on the back of shrinking household sizes. This building boom more than almost any other economic factor underpinned the job creation and rapid growth that accelerated the economy out of the grip of the Great Depression.

Home ownership rose from about 10% before the Great War to about a third by the start of WWII. No wonder there are many within the house building fraternity and elsewhere salivating at the idea of a return to those times.

The attractiveness of a major upswing in house building is great. I believe and have argued for the past three to four years that more needs to be done to encourage at least a doubling in the house-building numbers we see today.

There is however one huge flaw in harking back to the 1930s.

The similarities are many and inescapable between the early 1930s and today.

The economy was far below its previous peak level. Unemployment rates were rising and peaked at above 20%. Thankfully we are not so cursed.

There was a huge public sector debt as a result of the war, far larger as a proportion of national output than we have today. It was not the same measure admittedly, but probably about twice as big as today’s debt in relation of GDP and it was growing.

The policy response in 1932 was for the Bank of England to push down its interest rate to 2%, equalling the lowest level achieved before, having raised rates in 1931. The 2% rate was held until 1939.

That all sounds a bit familiar. But, and here’s the flaw, there were huge differences.

The building societies had accumulated strong reserves during the Great War and were eager to lend.

Land was cheap, even for the more expensive suburban sites the plot cost at 25 homes per hectare could be a matter of less than 2% of the sale price of a home.

The rental market had been regulated during the war and investment here was falling away. This is pretty much a reversal of what has been happening in recent years.

But the most important difference between then and now is that then a massive swathe of the population suddenly came into the scope of home ownership, today home ownership levels are falling.

A pretty average worker with good saving habits could buy from scratch a three-bed semi with a reasonable garden in 1935. The general deal in the 1930s was three times the man’s earnings and a 10% deposit. Theoretically there were 95% mortgages and they were advertised and available, but most of the anecdotal evidence suggests 10% was the norm.

This meant that an average semi-skilled or skilled worker earning between £150 and (possibly up to) £200 a year could aspire to buying one of the £500 to £550 three-bed semis that seemed to dominate the market in the rapidly expanding London suburbs.

This opened up a huge new market of both young and established families keen to live in a spacious modern home. And this massive new market supported the boom in building.

Today the second-hand market accounts for 90% of house sales. A prospective buyer would be expected to trade up the housing ladder building equity as they traded. And the market for new entrants has narrowed as home ownership has swollen over the past 80 years.

Of concern too, the number of first-time buyers has been in retreat for a decade, as prices increased and put house ownership out of the reach of more and more young people.

Between 2001 and 2004 the number of first-time buyer loans fell from 568,200 to 358,100, according to figures from the Council of Mortgage Lenders. This happened despite tempting teaser rates, cash-back incentives, historically low deposits and a near frenzy to buy into the housing market.

Today the idea that the mainstream new entrants to the housing market might buy straight in at the level of a three-bed suburban semi seems pretty fanciful.

The average price of a new-build semi today in the South East is around £270,000, according to NHBC figures. If bought on the same basis as was the norm in the mid 1930s, it would mean the main earner bringing home a salary of £80,000 and stumping up £27,000 in deposit.

Median earnings in the South East stand at about £32,000 for men and just below £24,000 for women. Even on a joint income basis the median earning household is well out of the game.

This does not mean that the so minded should abandon hope and stop campaigning for more house building. We need more homes.

But, on the above figures, it would seem that if we want a new house-building boom we will need a far more ingenious and powerful set of market prompts than promoting a greater availability of higher loan-to-value mortgages, freeing up planning and continuing to supply mortgages at low interest rates.

One thought on “Why a 1930s style private-sector house-building boom seems highly unlikely”

Added to all of the above were the facts that :

1) World commodity prices were depressed meaning both land and materials were available at historically low prices.

2) There was ‘surplus’ labour available as a result of migration to the South East from the regions.

3) Planning obligations were unknown, and the state had to shoulder responsibility for providing the necessary physical and social infrastructure after developments had been completed.

Comments are closed.